ALBUM REVIEW: Bob Dylan shoots himself into the canon on ‘Rough and Rowdy Ways’

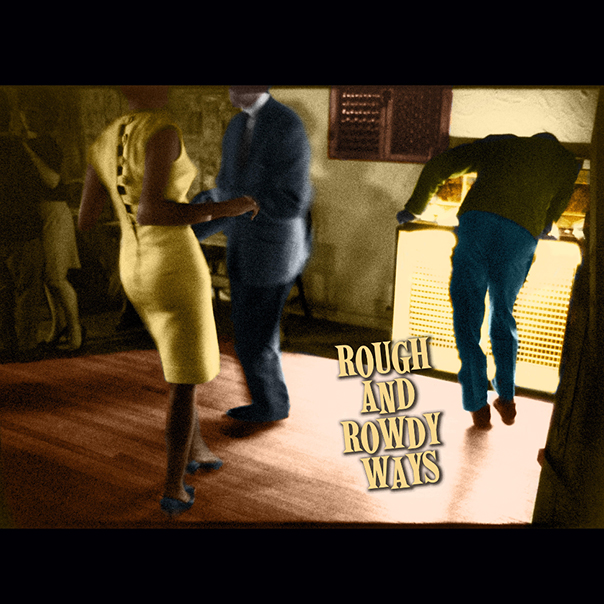

Bob Dylan, “Rough and Rowdy Ways.”

In the 1919 essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” poet T.S. Eliot writes, “No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists. You cannot value him alone; you must set him, for contrast and comparison, among the dead.” The steely, inscrutable stare of Bob Dylan has been studied almost as much as the Mona Lisa’s wry smile. For decades and without much success, fans, scholars and critics have searched those cold blue eyes for a trace of the fire burning within, wondering what fuels it and what shelters it from the wind’s quickly changing ways of blowing.

Rough and Rowdy Ways

Bob Dylan

Columbia Records, June 19

Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan’s latest album, suggests that unreadable gaze is searching for a place in history. Dylan is looking beyond us mere mortals who will turn to dust long before the ripples Robert Zimmerman cast in our pond subside. The new album feels like a shot at the history books. He seems uniquely cognizant of his place in the traditions of both poetry and music, and the album feels in many ways like a newly treasured volume seeking space on a bookshelf already crowded with greats.

Like T.S. Eliot, Dylan often mentions his influences explicitly in his lyrics. This includes Eliot, whom Dylan cast in 1965’s “Desolation Row,” singing, “And Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot/ Fighting in the captain’s tower/ While calypso singers laugh at them.”

On “I Contain Multitudes,” Rough and Rowdy Ways‘ opening track, Dylan compares himself to a diverse cast—including Edgar Allen Poe, William Blake, Anne Frank and the fictional Indiana Jones—in order to describe the largeness of his identity with the song title’s allusion to Walt Whitman (“Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then I contradict myself/ (I am large, I contain multitudes),” Whitman wrote around 1855). In the second verse, Dylan sings: “Got a tell-tale heart, like Mr. Poe/ Got skeletons in the walls of people you know/ I’ll drink to the truth and the things we said/ I’ll drink to the man that shares your bed/ I paint landscapes, and I paint nudes/ I contain multitudes.”

The music is, for lack of a better word, theatrical. The acoustic guitar on “I Contain Multitudes” lays gently in a bed of strings and pedal steel that rise and fall with the lyrical tensions. Dylan’s voice sounds weathered and gravelly. Imagine a Jewish Louis Armstrong delivering a heartfelt musical message at the end of a Coen Brothers movie. It may seem a bit of a stretch, but that’s the vibe.

The album moves through various musical moods, but Dylan seems at home in all of them. Whether the tremolo-laden twang of “False Prophet,” the delicate and lilting “Oooohs” of “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself To You,” or the grim piano and strings that lead the listening through the nearly 17-minute funereal ode to JFK, “Murder Most Foul,” Dylan seems dreamily at ease and catlike: in musical terms, if he fits, he sits.

And when he sits, he makes it work.

While Bob Dylan travels through the various musical moods, there is very little sense of “freewheelin.'” He and his listeners do not arrive at these musical destinations by accident or happenstance. These various musical jaunts feel intensely purposeful, as if Dylan knows precisely what he wants to accomplish.

Rough and Rowdy Ways is, at its core, the product of a deeply mature artist. Dylan is no longer a musical geyser, erupting irregularly with whatever material was building inside of him. His 39th studio album, and his first since 2012, is a testament to intentionality.

A little more than a century after T.S. Eliot emphasized the power of artistic tradition, Dylan seems eager to take his place in the long line of poets and songwriters that stretch toward eternity in both the past and future. Dylan is now writing with what Eliot called “a historical sense.”

“The historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence,” the poet wrote. “The historical sense compels a man to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order.”

Follow writer David Gill at Twitter.com/songotaku and Instagram/songotaku.