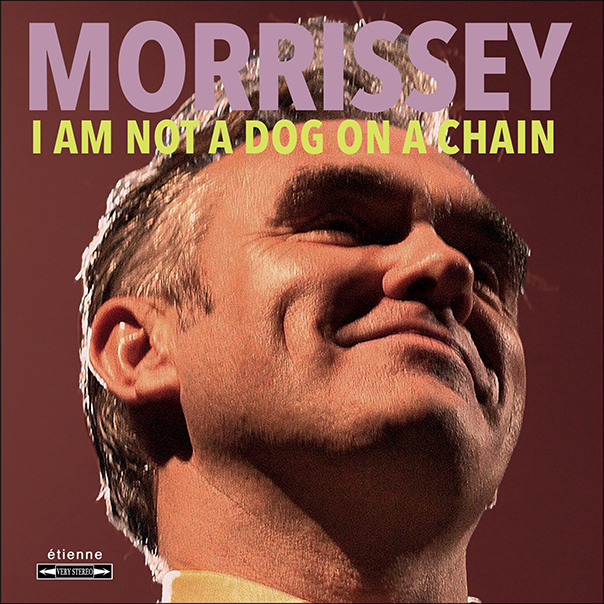

ALBUM REVIEW: Morrissey goes for blood on ‘I Am Not A Dog On A Chain’

British singer-songwriter Morrissey thrives on the psychologically dubious. A flavor of malice runs through his work, lacing his sincere efforts in song-poetry with danger and distrust. So it is a bit of a departure when he asserts his curmudgeonliness with heightened directness on the title track of his new album, I Am Not A Dog On A Chain.

I Am Not A Dog On A Chain

Morrissey

BMG, March 20

Morrissey ploughs an elder’s furrow of self-assuredness across his catalog of elusive meanings and obscure turns of phrase. Even the declarative statement headlining the album and title track remains subject to interpretive doubts. Is he not a dog, or not on a chain? But this time out, he allows himself to be outwardly dangerous, rather than hiding a spiteful barb in flowery verse and wretchedness.

The most gripping evidence of this forthright approach leaps out on passionate opener “Jim Jim Falls.” Scuzzy synth slices forcefully, hitting like minimal Detroit techno before venturing into atonality with a screeching guitar solo and the dramatic pull of layered strings. Morrissey disqualifies himself from every counseling job on earth with the shocking chorus: “If you’re gonna kill yourself, then to save face, get on with it.” No less, he follows it up with the sample-ready refrain, “just kill yourself.”

Questionable taste flavors much of Morrissey’s menu, and that he would use the most anthemic chorus on the album to serve up such a sick sentiment is not quite unexpected. As cutting as his words may be, he chooses them carefully. His vitriol, here as elsewhere, is not entirely groundless. “If you’re gonna run home and cry, then don’t waste my time,” he snarls, reasonably dismissing the self-pitying in a line to which most listeners can surely relate.

Despite the caustic phrasing, the theme on “Jim Jim Falls” and throughout I Am Not A Dog On A Chain revolves around strength in personal validity and identity. Likely, Morrissey trusts his listeners not to self-harm, and offers reassurances to guide the way over. “Open up your nervous mouth and feel the words come streaming out … otherwise, you’ll never know who you are or all that you can do,” he urges on the title track. Morrissey sets an expectation of defining oneself in opposition to melancholy or resignation, his reputation notwithstanding.

But neither is he all righteousness and uprising. In statement and style, the fine “Love Is On Its Way Out” strikes a grandiose pose in the name of a different virtue. Though not specific about how he defines love, Morrissey offhandedly remarks on its moribund state. “Did you see the sad rich hunting down, shooting down elephants and lions?” he sings, drawing an elegant parallel between persecutions of the natural. The fatalistic overtones turn manipulative, however, as Morrissey pivots to a hard plea. “Love is on its way out,” he mourns, but “before it goes, do you have the time to show me, what’s it like?”

Musically, the album serves as a theatrical backdrop for Morrissey’s unique voice and persona. The tone is brash and strident throughout, but cold. The instrumentation dwells overwhelmingly in something of an obsolete synthesizer sound. Broad brassy synth maneuvers provide the glue over punchy, straightforward drumbeats. Guitar is used as a garnish, most often to add jangle but also for the odd attitude-soaked lead. Abstract, ethereal backing vocals elevate “My Hurling Days Are Done” and grower “Darling, I Hug A Pillow,” which gains cinematic momentum despite strange, faltering trumpets.

Fans of The Smiths may be disappointed by the direction of Morrissey’s latest. The closest Morrissey comes here to his former band’s jangle-rock sound is “What Kind Of People Live In These Houses?” It bounds with the summery optimism of “Cemetery Gates.” Still, this song, and in fact everything on the album, is mixed for the dance hall rather than the rock club. In service to Morrissey’s voice and clever lyrics, the instrumentation veers toward the cinematic. It’s less rock, and more some kind of austere orchestral pop.

The full-blooded, strident tone of the album comes through in a handful of strong tunes, like lead single “Bobby, Don’t You Think They Know?” The song echoes classic Eurythmics, thanks to the welcome co-lead vocals of Thelma Houston and a tough, sweaty discothéque arrangement. “Knockabout World” sounds like a lost pop hit from the 1980s, while the lengthy “The Secret Of Music” is an unusual funk jam. The cold strobe of “Once I Saw The River Clean” reflects the gloomy Mancunian atmosphere of some of Morrissey’s earliest recordings. Changing gears for a bounding chorus, the song is emblematic of the techno-rooted, dark pop style prevalent on I Am Not A Dog On A Chain.

To the casual listener, Morrissey has always been a bit much to bear. The tedious rhyme scheme and alliteration that opens the fraught “The Truth About Ruth” represents Morrissey at his most suffocating. His lyrics, while usually thought-provoking, do at times stew in cynicism and pedantry. But that cynical stew is Morrissey’s signature dish, and it’s certainly proved popular and singular enough to sustain him as a working artist. Chain is less maudlin and more declarative than the majority of Morrissey’s work, and it features a strong batch of songs and ideas. A mature work, the album stands apart in his catalog, displaying a hard-fought air of confidence that defies his roots in misery.

Follow writer Alexander Baechle at Instagram.com/writheinsmoke.