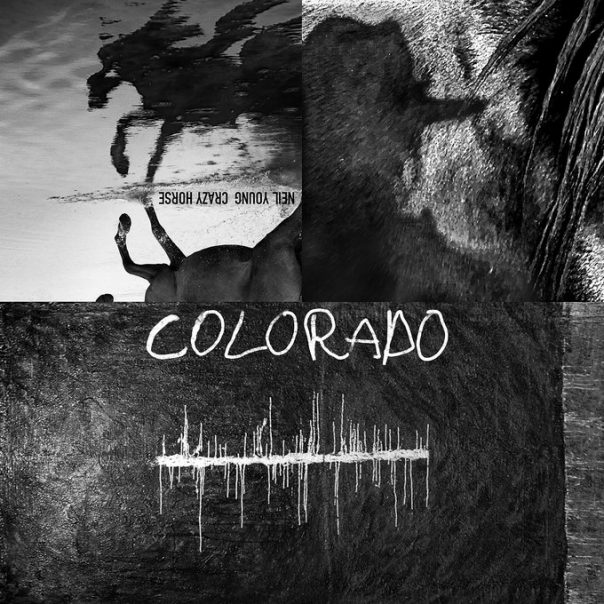

Neil Young & Crazy Horse contemplate stillness on ‘Colorado,’ accompanying film ‘Mountaintop’

The specter of aging looms over any rocker. Some age gracefully and lose significance. Others fail to grow out of youthful recklessness and find themselves in mid-career doldrums, leaving the rest to fade away as self-parodies. Neil Young continues his pondering on the significance of mortality with the same ethos that helped him blaze his career path. Recorded with his band Crazy Horse for the first time since 2012’s Psychedelic Pill, Colorado shows Young can age well without sacrificing his roots in cacophonous rock.

Colorado

Neil Young & Crazy Horse

Warner/Reprise, Oct. 25

Long after cleaving tenaciously through the ’60s hippie ideals, Young remains a prolific recording artist as he approaches his mid-70s. Recorded with few overdubs in a rented lodge outside Telluride, Colorado pays tribute to familiar subject matter. Young’s rumbling guitar and passionate leads, the resilient rhythm section of bassist Billy Talbot and drummer Ralph Molina, and rockpile vocal harmonies emerge from deep earthen recesses. Young roves through his usual range of styles, including extended electric jams, acoustic numbers and piano-driven reflections.

Surging harmonica heralds the blues-tinged shuffle of “Think Of Me.” Over these optimistic sonics, Young relates a relationship to exploring the natural world: “I can gallop across your open prairie/ While I dive beneath your deepest sea/ Think of me.” Electric guitars then change the pace and augment the album’s flow. Where 2012’s sprawling Psychedelic Pill centered on long-winded songs, the only song on Colorado that exceeds 10 minutes is “She Showed Me Love.” The lengthy track is Young in his ear-bleeding element, featuring massive guitar solos and a reverent chorus.

Though a folk singer at heart, Neil Young follows the crushing form of previous albums with Crazy Horse. Over the scalding chords of “Shut It Down,” he shouts a critique at those who profit from ignoring climate change. As with other recent Young records, his statements defend nature, combining topical issues with contemplations on the stillness and immensity that accompanies seniority.

Guitar exercise “Milky Way” lands halfway between the licks of “Southern Man” and the hazy shambling of “On The Beach.” Young’s voice wavers with the delicate delivery of the refrain: “As the stars flew by I did collide with memory but somehow I survived.” He imagines floating untethered in the universe.

Crazy Horse sets itself apart from Neil Young’s other collaborators with a monumental, almost choral use of vocal harmony. Molina, in particular, sings his heart out to recreate this signature element of Crazy Horse. Meanwhile, guitarist and pianist Nils Lofgren rejoins the effort, having previously worked with both Young and Crazy Horse. Colorado marks his first official album credit as a member of the band.

Conciding with the album’s cinematic nature, a making-of documentary companion film accompanies Colorado. Titled Mountaintop, it focuses on the album’s more raucous numbers. The film intersperses mountain vistas and concert footage into extensive coverage of the 11-day recording session. Watching the band stumble through “Help Me Lose My Mind” and “Olden Days” early on is an interesting vantage point. During “Help Me Lose My Mind,” Young rails against the monitor, telling an engineer, “I want it up as loud as it can go… I want to hear the fuckin’ thing. This is not a fuckin’ recording, this is a band.” He wanted that vital loudness, along with the live quality from which Colorado benefits.

Footage of recording the vocals to the chorus of “She Showed Me Love” details an agreeable and impressive moment, but the challenges of Young’s approach are evident. Producer John Hanlon almost loses it over the faulty wiring in the studio, but reels it in in time to salvage the session. Young relies heavily on acerbic phrases and expletives to get his points across, providing insight into the album’s spontaneous sound and immediate acoustics.

Early in the film, Young and his band discuss the inclusion of a mistaken note in Nils Lofgren’s guitar playing on the anthemic “Rainbow of Colors.” Young is supportive: “Let’s just leave it for a while. We know we can fix it if we want to. Right now it’s … gold.” Young allows flexibility to preserve the spontaneity of a band performing live.

“Doesn’t have to be good, just great,” Young says matter-of-factly, and Lofgren concurs, adding, “There’s a charm to it.”

The film sheds light on this rock ‘luminary’s journey to make what he wants, his way. His band and production team obviously know better than to argue with his vision, weathering his paroxysms patiently in the interest of making a quality album. Young leads Colorado’s recording process with an ear for quality and an eye on the clock, exhibiting total control over the pace of the session. His focused observations translate swimmingly onto the album.

Though intimate at its core, Colorado is deceptively diverse. While there is no shortage of cacophonous rock, gentle cuts like “Eternity” and “Green Is Blue” provide useful variations. The peaceful “I Do,” centered on a major seventh chord, ends the record with an expression of gratitude and long experience. Young’s harmonica returns briefly, this time echoing the lonely heights and slot canyons of the Rockies.

Young’s collaborations with Crazy Horse give him an outlet for his take on high-decibel arena rock. It’s the perfect balance for his sentimental folk songs. He seems to thrive on discomfort. As seen in Mountaintop, the oft-caustic studio atmosphere pushes those moments of unhinged passion.

The tension is symbolized in another encounter between Young and his foe, the monitor. He calls it, “one of the worst fuckin’ monitoring systems known to man.” He then causes it to feedback painfully to support his claim. “Rock and roll was built on that,” he says, creating a harmonious contradiction. Colorado‘s malfunctions ended up furthering its road-weary beauty.

Follow writer Alexander Baechle at Instagram.com/writheinsmoke.