ALBUM REVIEW: Sufjan Stevens perfects avant-romanticism on ballet score ‘The Decalogue’

Deep diving into Sufjan Stevens’ catalog reveals he’s far more than an indie folk visionary—from collaborative space operas and glitched-out indietronica to Grammy-nominated soundtrack contributions. So his stints in ballet scoring shouldn’t surprise anyone. In fact, The Decalogue isn’t even his first time working with choreographer Justin Peck for the New York City Ballet.

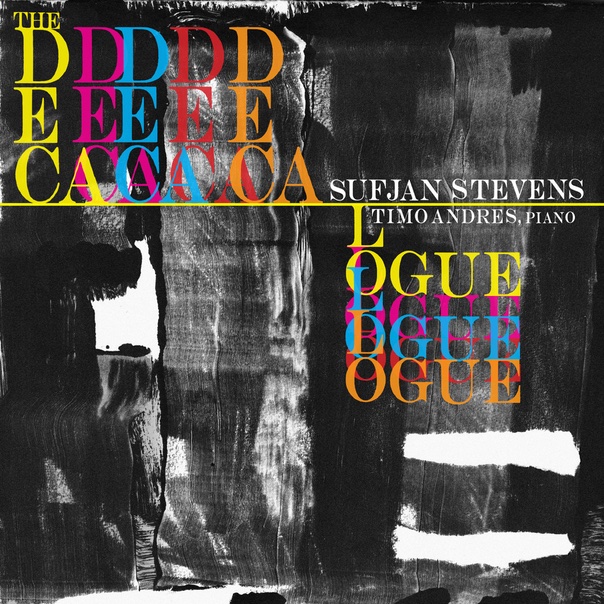

The Decalogue

Sufjan Stevens, Timo Andres

Asthmatic Kitty Records, Oct. 18

As the name suggests, the ballet centers around the biblical Ten Commandments—a dichotomous foundation for unorthodox music and choreography. Presented in LP form two years after the ballet premiered, The Decalogue sees pianist Timo Andres bring Stevens’ vision to life in a flurry of impressionistic romanticism.

The abject minimalism of these 10 compositions is clear immediately. It’s fitting that Surfjan Stevens packaged the album with a notated songbook in limited run of LPs, in that you could see this making many graduate conservatory students’ recitals. It’s fun to imagine how those who know Stevens for “Fourth of July” and “Love Yourself” would think of singles “III” and “IV.” The former vaguely recalls the more technical works of Johann Sebastian Bach, while the latter comes off like a protracted take on “Clair De Lune.” Both tracks set a nonlinear, stream of consciousness for Stevens’ album to follow.

While its cadence lends itself to the ballet medium, the music takes on a life of its own when taken on face value. The clanging modulations of “I” exhibit Andres’ ability to emphasize the percussive elements of his instrument, while the drizzling arpeggios of “II” display his nimble dynamism. Sufjan Stevens’ arrangements stay on their toes, constantly shifting keys and never fully resolving its ideas. While the lack of overt cohesion can make these songs hard to follow, Stevens’ choices are thought out.

Though unconventional, The Decalogue has no shortage of profound beauty. “V” is an obvious highlight in this regard. Its tumbling crescendos and delicate chimes overflow with resonance and power. In contrast, the haunting dissonance of “VIII” might call minimalist experimentalists like Goldmund to mind. These less accessible passages have no lack no emotion, using a lack of boundaries to express what no one else can. Cohesion can be found within more bombastic bombastic cuts like “VI”—thought it’s in timbre and structure rather than melody. Andres rarely plays the same chord, melody or harmony twice—a testament to Stevens’ disregard for classical dogma.

These songs aren’t meant to get stuck in your head, but to put you in a certain headspace. “VII” returns to a more technical choppiness, where each phrase will lead remains a mystery. From sudden dynamic and tempo fluctuations to curveball melodic runs, the song remains compelling in its unpredictability. Though much more of a slow-burner, “IX” uses the extra space between notes to let each harmony resound in colorful inventiveness. Its transition to acrobatic scale runs, while unprecedented, recall romanticism with its over-the-top bravado. Even when it veers closer to atonality, this score’s strange beauty is truly a treat to the ear.

After such a tumultuous journey, the fact the final notes of “X” provide a sense of satisfying closure becomes a surprise. Like feeding Ludwig van Beethoven at his most rigorous and Frédéric Chopin at his most ethereal through a sonic kaleidoscope, the song encapsulates what makes Stevens special as a classical composer. His boundless sense of arrangement never comes at the expense of thematic grandior. He and Andres are poised to give romantic piano music a much-needed revival in the public consciousness.

Follow editor Max Heilman at Twitter.com/madmaxx1995 and Instagram.com/maxlikessound.