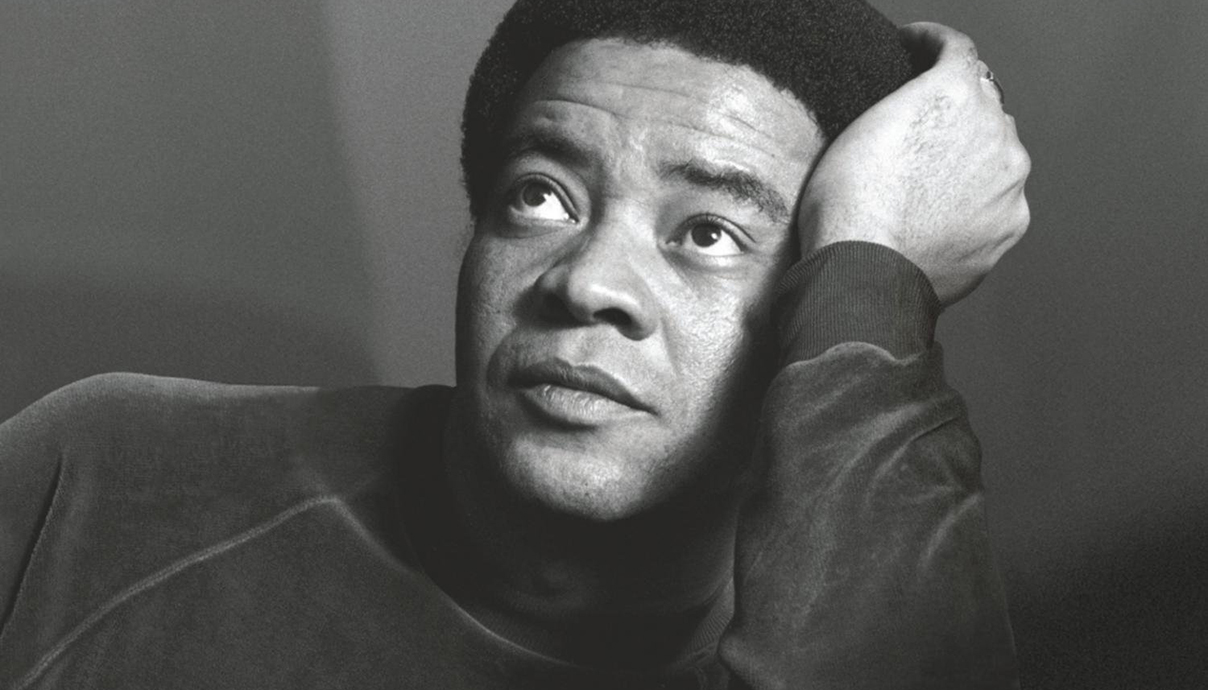

Obituary: Bill Withers had rare gifts for a regular guy

I didn’t know Bill Withers was black until I’d already come to know his music. As a kid, I constantly confused him with Van Morrison all the time. And I’d seen Morrison on television, so …

That’s a huge compliment. To both of them. It was music sounding straight from the human soul, no detour and not labeled or lumped into a preconceived identity.

And it’s also indicative of how underrated and seemingly uninterested in self-promotion Withers was.

The composer of songs like “Lovely Day,” Ain’t No Sunshine,” “Lean on Me,” “Just the Two of Us” and so many more died Monday in Los Angeles, from heart complications. He was 81.

Withers wasn’t the typical musical success story.

He grew up in a small town in West Virginia, the youngest of six children. He joined the Navy after high school and ended up in California. After working as a milkman in Santa Clara County and at an aircraft factory, he was inspired after seeing Lou Rawls perform at a club in Oakland. He taught himself how to play guitar and begin writing songs. According to Rolling Stone, he wrote “Ain’t No Sunshine” after watching the Jack Lemmon film “Days of Wine and Roses” on television.

Decades later, he told the magazine he still was amazed at his success coming relatively late in life. “Imagine 40,000 people at a stadium watching a football game,” he said. “About 10,000 of them think they can play quarterback. Three of them probably could. I guess I was one of those three.”

Withers may have been the smoothest soul singer-songwriter who ever exuded a genuine “who me?” attitude. Withers was a musical phantom, the wizard with the gorgeously warm voice whose influence was everywhere while he remained behind an anonymous curtain of his own making.

The epitome of an everyman; his first two albums were called 1971’s “Just as I Am,” and 1972’s “Still Bill.”

He himself seemed surprised by his abilities.

Shortly after getting the news he was elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2015, Withers told Rolling Stone, “I still have to process this. You know that Billy Joel line, ‘Hot funk, cool punk, even if it’s old junk, it’s still rock & roll to me?’ I’m happy to represent the old junk category.”

But he didn’t care for fame. He hated touring and didn’t trust the music industry. He retired for good after making one last record in 1985 and said he had no regrets, living nicely with his wife off song royalties and sound investments. Anyone trying to cover Withers–and there’s been thousands–knows they better mean what they sing and have the voice to back it up.

He came out of retirement once, in 2004, for the 40th birthday party for Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores. “His wife kept calling,” he told Rolling Stone. “She said it was only for 150 people, but I kept refusing. Then the (money) got so high that my nose started to bleed.”

Withers’ 70s catalog has weathered time as well as any of his contemporaries, as evidenced by how much it was being passed around online, even before his death was announced, as people huddle in isolation during the recent COVID-19 outbreak. Withers’ voice is welcome right now; like someone’s favorite uncle with the wisdom of years and the warmth to convince us everything is going to be all right.

Thanks, Bill.

Follow music critic Tony Hicks at Twitter.com/TonyBaloney1967.