A tour of Nashville with Camaron Ochs, two years after the tornado

Camaron Ochs photographed at Ryman Auditorium in Nashville on Sept. 26, 2018. Courtesy Chelsea Kornse. Other photos: Roman Gokhman, unless noted.

NASHVILLE — It wouldn’t be obvious to this outsider, until Pamela Cole, co-owner of Fanny’s House of Music guitar store in East Nashville, points to a photo pinned on a wall.

“It was two years ago, on March 3,” Cole says. “The tornado went right through here. It went right down this street,” she points. “[The building] was damaged. Then COVID closed us two weeks later.”

Fanny’s, which is geared toward women, girls and nonbinary musicians and future musicians, is located inside an old home near the corner of Holly and South 11th streets. Cole and a friend (currently home battling COVID-19) opened the store about 14 years ago. When the tornado barreled down on it, all the windows and doors were blown in. Some art, like a popular mural featuring famous women guitarists, was damaged.

“Only one guitar was damaged,” Cole says. “A 100-year-old guitar, gently placed on the ground. It was weird. That wall [she points] almost blew out. It buckled. But it’s like the place … we’re divinely protected, somehow.”

Fanny’s store and the surrounding neighborhood in the days following devastating tornado in Nashville on March 3, 2020. Courtesy Fanny’s.

The photograph shows the damage. Suddenly, I understand where I am. It now makes sense why every third or fourth building in the area is under construction.

Fanny’s is the first place Bay Area (Lafayette) native Camaron Ochs—better known as Cam—takes me during a tour of “her” Nashville. Ochs, who’s lived here for about a decade now, is a hit songwriter, a successful musician and performer in her own right, and, it turns out, on the Fanny’s advisory council (along with the likes of Brittany Howard of Alabama Shakes). She’s trying to help Cole expand beyond its three small music lesson studios and build a school out back.

“Have you ever been to a Guitar Center? I don’t know if you can tell, but it’s kind of bro-ey,” Ochs says. “A lot of barriers to getting an instrument, let alone playing, and then the whole business is slanted. … I’m trying to help in small ways that I can.”

“She’s wonderful,” Cole adds about Ochs.

This is my last of four days in Nashville. I’d flown into Charlotte a week prior, drove through Chimney Rock and other beautiful wilderness areas to a corner of South Carolina to adopt my family’s new puppy, Sunflower. The two of us then drove to Atlanta, spent a few hours in Rock City in Chattanooga and finally ended up in Nashville. Of America’s major music cities, it was the only one I’d never visited. I needed a guide, and Cam raised her hand.

Actually, several helpful people in my digital Rolodex raised their hands, and because of this, I got a warm welcome, with tours of the Grand Ole Opry and Ryman Auditorium—and a front row, center seat for Three Dog Night’s show at the Ryman—two different Old Town Trolley tours (one that focused on the city’s history and tourism, the other on its music) and lunch at Blake Shelton’s Ole Red, one of the celebrity-branded bars on the most congested two blocks in the city: Broadway.

Athens of the South, home of Little Richard

“There are 8,000 songwriters in Nashville; 30 of them are making a living. The rest of us make $120,” says “Bert with an E,” the narrator on my Soul of the City trolley tour. Bert sold a song to a country artist and collects about $120 for it every year.

He’s also a former entertainer on Princess Cruises. That makes him perfectly suited to talk about the lesser-known stories of Nashville’s music history while playing catchy covers on a keyboard that he folded down from the wall of the trolley.

Bert and Adrian (“with two A’s”) are a two-man comedy act, too. The trolley quickly covers the basics of Broadway—all these honky-tonks here live off of covers, and there’s about three places (including the famous Bluebird Café; not downtown) where songwriters try to get discovered with original songs.

He covers the artist-branded bars. Everyone who’s anyone seems to have one; Miranda Lambert’s is one of the newest (and supposedly she pops in more frequently than others) but there’s also Jason Aldean and Kid Rock, who’s apparently gotten kicked out of his own place not once but twice. That seems on-brand.

We then hightail it out of the area before we can get stuck in traffic. We learn about Jefferson Street (“It had its roots in the plantation days”), which is the home of rock, soul, R&B and jazz in Nashville. We learn about how Nashville has been in the habit of destroying historic buildings and building over them. We pass by EXIT/IN, the first club to play anything other than country in the city. Then there’s the collection of residential-looking buildings and offices that house Music Row, the home of the music industry. I’d driven by there by myself the previous day, but without the narrative, saw nothing.

“What’s Nashville known for besides alcohol?” Bert asks, which leads to a story about how while it’s known for music, medical care is the No. 1 industry in the city. There are hospitals everywhere.

The following day, I’ll go on Old Town Trolley’s main hop on/hop off tour, which includes a wider angle of the city and its attractions, including the historic Marathon Motor Works, full-scale concrete Parthenon (Nashville had the first university in the South, and has been known as the Athens of the South), the state capitol and Belmont University and Mansion, but music still plays a crucial role in the storytelling of my driver.

He happily points out the penthouse where Little Richard lived, and how he loved to let his fans know when he was around. It turns out that he loved to hang out on the street and give out autographed cards, once offering my driver 12 of them.

As we’re passing Bridgestone Arena on Broadway, the driver mentions it’s the No. 2 arena in terms of tickets sold in the U.S. (second to Madison Square Garden).

“That’s before the 2021 numbers. I’m thinking coronavirus might have made us No. 1!” he shouts.

He points out the cranes across the skyline and tells us to Google “Nashville crane tornado.” When the tornado struck two years ago, there was a scared worker who didn’t have enough time to make the 20-minute descent. Being smart, he called his wife and asked what he should do. She told him to stay in the crane and wait it out, hoping it was strong enough to stay upright…

Broadway

Other than morning time, Broadway seems to constantly be an overwhelming place, with thousands of tourists packing its two blocks and live music blaring from every restaurant and honky-tonk through speakers hanging on light poles.

I visit all four days at different times, but I don’t stay long. Parking is hard to come by. The garages aren’t cheap.

Cam’s favorite honky-tonk on Broadway is Robert’s Western World.

“It has a bunch of old boots on the wall, and it feels actually western, like when people would call it country and western, less so than the new age,” she says.

But she usually avoids the area. Touring artists, in general, need to learn how to manage their offstage time to not go off the rails with a party lifestyle.

“There was a short time I was single here, and ‘Come on down, meet somebody. They’re going to be gone pretty soon,’” she says, laughing. “It’s a pretty heavy drinking lifestyle. People come here kind of like Vegas. They’re not even going to act like themselves on a day-to-day basis. They’re going to be the most debaucherous version of themselves. If you drive through here or walk through here at 2 in the morning, people are just peeing on the sidewalk. I’m not against having a good time, but that kind of time?”

I walk through several Western stores full of boots and crowded to the brim with tourists, check out a bar where a musician is playing Petty and Dylan on a resonator guitar, check out the Johnny Cash Museum (also too crowded) and then head to Ole Red, Blake Shelton’s club, where I’ve been invited for lunch.

The place is huge, about five floors in all, with a rooftop bar somewhere. I stick to the main performance area on floors 1 and 2, where Chris Ruediger and his band are playing covers of everyone from Prince to Willie Nelson and Johnny Cash. The lighting and staging are top-notch. There’s a tractor hanging upside down from above the stage.

I’m no food critic, but my burger, artisanal tater tots, honey cornbread and strawberry shortbread taste great. Manager Ryan Styck tells me that Shelton comes in from time to time, sometimes to play himself. There’s music from opening to closing. Some young attendees on the second floor are trying to float some bills down into Ruediger’s bucket on the stage and he gamely plays along. My waitress is friendly and curious about where I’m from.

Rep John Lewis Way street sign near the Woolworth’s building where Lewis led sit-ins in the 1960s, photographed on Feb. 13, 2022.

Rep. John Lewis Way

As Cam drives us, she points out the gay bars on Church Street and the churches on Gay Street. She expertly parallel parks on Rep. John Lewis Way and we get out in front of the old Woolworth’s building, where Lewis and others used to lead sit-ins that eventually desegregated several businesses. The store only recently closed and will eventually become a theater.

“That was the beginning of change,” she says.

The city is peppered with historical markers. Significant events happened all over the place, and I’ve visited a few of them in addition to my music and culture experience here. Cam asks herself often who makes the decisions for these markers and monuments. She points out that in the cemetery across the street from her studio, there’s a marker for the first white child to be born in Nashville.

“We just removed a bust for Nathan Bedford-Forrest, the guy who started the Ku Klux Klan from the [state] capitol. Who decides what stays and what goes?” she says. “It was a big victory for young and old activists that have been working so hard for just a symbol. That doesn’t mean life’s better. … The city’s like 30 percent Black, and their experiences here and what opportunities they have and all that stuff—did all that change the day they removed the bust from the capitol? No. But it’s a very small gesture. It was a big deal. It’s wild to think about.”

Cam drives us by the newish Ascend Amphitheater along the Cumberland River—“Even if you don’t buy tickets, you can kind of be across the street and hear it all going down”—before driving through downtown, which she says has been gentrifying for a while. Ten years ago, there was no Whole Foods in the area.

Now it’s not uncommon to see Tim McGraw and Faith Hill shopping at one, she says. No one bothers them or the other well-known musicians. Nashville is not L.A.

“TMZ tried to put an office in here, and they basically got run out of town,” she says. “Everyone is just down to take it easy, which is really nice.”

Still, Cam says she’ll get recognized from time to time. A few days prior, she explains, she was in a restaurant, sans makeup or her signature blonde curls, when a waitress passed a note scrawled on the back of a receipt from a fan.

A musician performs for tips at Whiskey Bent honky-tonk on Lower Broadway in Nashville on Feb. 13, 2022.

“She was like, ‘I didn’t want to bother you, but I just want you to know how much your music means to me.’ It was really sweet,” she says. “There’s a culture in Nashville that even if you do see someone you know, you just don’t bother them as much.”

But it’s generally not a good idea to broadcast yourself as an artist or songwriter to just anyone. She was once pitched music by her own optometrist during an appointment for contacts.

Ochs is also a fan herself. The Indigo Girls recently played at Ryman Auditorium and invited her to join them onstage.

“I’ve been obsessed with them for a long time,” she says, before explaining that she’s been a fan for years and even had the opportunity to say hi to them at a show at the Greek in Berkeley years earlier. Her mom pressed her to tell them how much their music meant to her, but she panicked and didn’t.

Later, she got to write with Emily Saliers.

“I adore her. She always jokes, ‘We get along so well.’ And I’m like [whispers], ‘You made me!’ Then we’re on stage at the Ryman and I got to tell the story of how I saw them at the Greek, and I’m like, ‘Now I want to tell you what you mean to me. It’s like this—that’s what I wanted you to know.’”

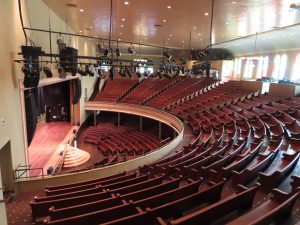

The Ryman is Cam’s favorite place to play in Nashville. The red brick building was originally a church in the 1890s. It could originally fit 6,000 people to listen to sermons without any sound systems. That means the acoustic are amazing, Cam points out.

The pulpit was surrounded by rings of pews. The pews are still there, but the room has in essence been sliced in two to build a stage, and then, eventually a backstage. The Ryman was the fifth home of the Grand Ole Opry, but once the Opry left in the ‘70s for its new state-of-the-art home, it fell into disrepair.

It came close to being bulldozed, like so much history in the city, but was saved at the last moment and was renovated in the ‘90s. It’s got air conditioning now!

As I learn on a tour of the church just hours earlier, Emmy Lou Harris had a lot to do with saving it. When it was just a shuttered building, she recorded a beautiful live album—with a small crowd that was not allowed to sit under the balcony for fear it would fall and crush people—that reinvigorated interest.

The Ryman and the Grand Ole Opry

During the renovation, the building entrance was flipped to the other side (taking out the parking lot) and a modern new lobby was added, with bathrooms, meeting rooms and more. From the lobby, you pass through the original wall. As for the stained glass? The original building didn’t have that; that’s new. So are the backstage artist rooms.

The stage is relatively new, but the first few feet of wooden planks date back to 1951. My tour guide tells me that when the stage was being rebuilt in 1971, enough of the previous boards remained in good condition to save and preserve them. If you take a tour, they’ll take your photo next to those planks and give it to you for free.

Three nights before this, I attend a show in this grand old building. Three Dog Night is playing and I arrive unfashionably late (the parking…). Everyone is already seated, and the band is onstage. I’m not sure where to go, so I get an escort to my seat, in the front row, dead center. I can comfortably put both my hands on those old boards while I’m seated. There’s no photography and security pit at the Ryman. Everyone is expected to behave.

Three Dog Night, performs at Ryman Auditorium in Nashville on Feb. 12, 2022. The lighter-colored planks at the front of the stage are original to 1951.

Cam headlined the Ryman once and also performed a livestream during lockdowns.

“There was no crowd, which was terrifying. So you could kind of hear it echoing,” Cam says. “It felt like I was singing for ghosts, you know? Then you’re like, all the people who have sung, and breathed air and made physical indents in this building…”

As for the remaining parts of that 1951 Ryman stage floor? When the Opry left, they took a piece of that with them. It’s embedded onto the stage at the Opry House now, as a circle at the front of the stage.

Between my tours of the Ryman and the Opry, I learn all about this circle, which so many sing will be unbroken. As well as about Little Jimmy Dickens and Minnie Pearl and Roy Acuff. At the Opry I get to stand within the circle for a photo ($25 if I want to keep it), even as I’m told most artists decline the offer until they get to perform on the stage. They want to earn the honor to stand there.

I see Studio A, a large box-like room where TV shows like “Nashville” were taped, where “Hee Haw” was filmed at the end of its run, and where the Opry members hold their private parties and award presentations.

By the way, did you know some Opry members have mailboxes at the Opry, and fans are encouraged to send them fan mail? You don’t even have to put an address on your envelope. “Dolly Parton, Grand Ole Opry, Nashville” will do. She’ll get it the next time she comes in.

The Otherside

Next, Cam drives me to her studio, which is purposefully not on Music Row. She says she likes the disconnect from other artists and their art, which can get overwhelming. While Music Row encourages collaboration, collaboration has a way of homogenizing your sound. Cam wants to sound like herself.

Somehow, we’re already running out of time; I’m flying out in a few hours. So she rattles off some of her other favorite places around town that we won’t get to visit, like Old Made Good and High Class Hillbilly vintage stores, Black-owned coffee and doughnut shop Status Dough, Nicoletto’s (which makes its own pasta), Jack Brown’s Beer & Burger Joint (they offer an Elvis-style burger with peanut butter) and SideKicks Cafe in Madison, northeast of Nashville, for its homey breakfast and lunch.

She says the city’s love of the popular Mas Tacos is warranted, but her favorite restaurant overall is East Side Banh Mi.

“When I get it on Postmates for the studio… I’m one of the top 1 percent of people that eat at this place,” she says, laughing.

Ochs’ studio is on an unassuming street across the street from a cemetery, with the aforementioned first white child to be born in Nashville and a woman who was named Lady Savage Butts. On breaks from recording, Cam, producer Nick Lobel and their friends and colleagues like to walk around and read the headstones.

Editor Roman Gokhman and Sunflower the puppy at the drum kit used to track Harry Styles’ “Watermelon Sugar” inside Cam’s studio in Nashville on Feb. 15, 2022. Photo: Camaron Ochs.

Lobel, who also mixed and engineered Cam’s last album, The Otherside, is here now. He and Ochs first point out the drumkit used to track Harry Styles’ “Watermelon Sugar.”

“That was written here, and we did some of the tracking here: the drums, and some guitars and some other instruments,” Lobel says. “That drum take; we set up the kit with some mugs and other kitchenware on it. I think there was even a sugar canister. That’s in the take. Mitch Rowland [Styles’ band member and cowriter] played drums on it. He played on mugs and cups and everything.”

As Lobel tells the story, there was talk of re-recording the part in L.A. Producer Tyler Johnson flew out to L.A. with all the cups and mugs to try to get the same tones, but they couldn’t recreate it and used the original recordings. The air quality must have been better in Nashville.

Lobel shows off his control room, which is being rewired, as well as the gear room run by the studio’s space-sharing company, Sphere, repairs and resells music equipment. The landlord of the studio, and also Sphere, just happens to be from Lafayette, Cam’s hometown.

The studio is comfortably furnished but always changing. The small reception area has several seats from a car, which were not there the last time Cam was there, she says.

“This is also where we wrote ‘Palace’ for the Sam Smith record. Sam came in, and we wrote it here,” she says.

Back on the East Side

Back across the Cumberland River and in East Nashville, she points out East Nashville Magnet High School, where Oprah went. Cam and her family get their Christmas tree from the school’s front lawn every year. She points out The 5 Spot, which plays old soul records on Monday nights and where an already famous Lady Gaga brought her Dive Bar Tour in 2016; and Dino’s, which serves up great burgers.

Does Cam get a chance to go out often?

“Not really, I guess. I’m socially, normally an introvert,” she says. “Then I can go out once in a little bit and spend all my energy. Country radio tour … when you get kicked into gear, you are traveling [a lot]. My husband and I had rule that we have to see each other every two weeks, and that was when we first started dating. It’s really hard to be home, and you’re exhausted when you do come home. Then you start touring, and now I have a kid and then there’s the pandemic. Every now and then, I go out and have a great time, and then probably you won’t see me for another three months.”

Cam is working on the follow-up to The Otherside now. It’s confusing for her because she hasn’t even toured that album yet. She had a tour scheduled for the top of the year but didn’t even announce it before canceling because of Omicron. It’s hard to make commitments now because a cancellation can leave her on the hook for $80,000 solely for a tour bus. But fans can expect to see her on the road sooner rather than later if we don’t keep learning new Greek letters.

At least the break from touring has allowed her to spend time with her husband and daughter, and focus her attention to causes important to her, like Fanny’s and the Women’s Audio Mission in San Francisco, the other organization she champions.

She calls Fanny’s a “grassroots mom and mom shop.”

The walls in the store are covered in photos of women guitarists. The only man with the honor is Dave Rawlings, “because we see him walk down the street all the time,” Cole says. There’s a wall dedicated to the owners’ mothers. There’s also a vintage clothing section.

“We want to empower young girls and women. Music stores have, most of the time, lots of dudes on the wall. We wanted it to be different,” Cole says.

“This is for non-men. This is a space that’s inclusive. This is a space that’s not just for white people,” Cam adds. “We’re saying that out loud.”

Follow editor Roman Gokhman at Twitter.com/RomiTheWriter.