Insert Foot: ‘Kintsukuroi’ explores shameful chapter in U.S. history not taught in schools

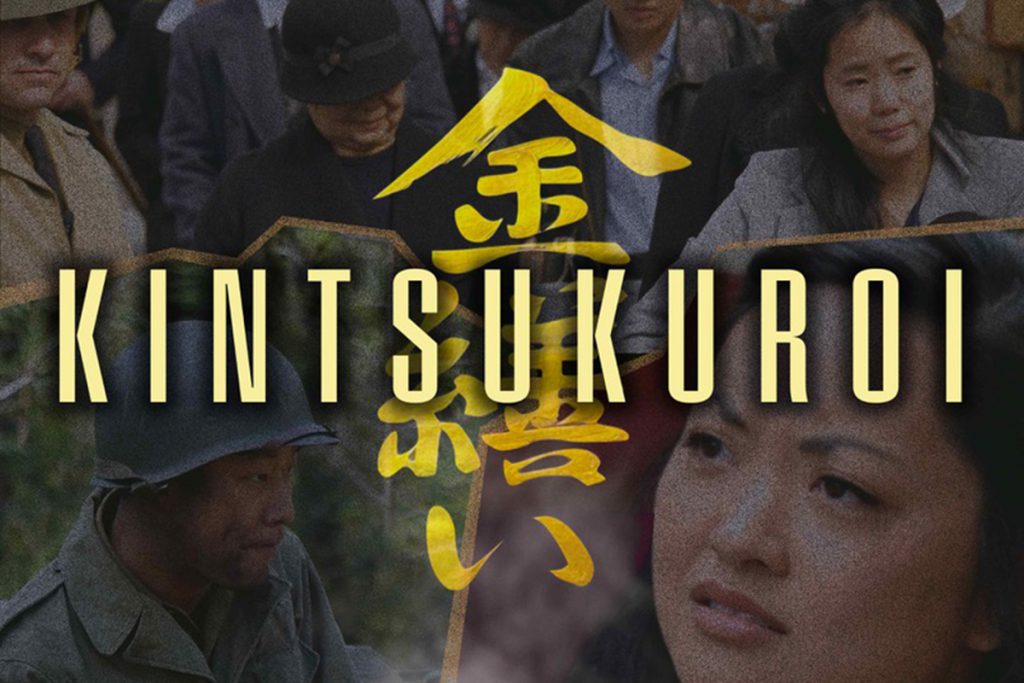

“Kintsukuroi” film art.

My 15-year-old daughter and I went to the San Francisco premiere of “Kintsukuroi” last weekend. It’s an independent film from director Kerwin Berk following members of the San Francisco Japanese American community the government rounded up and forced into internment camps during World War II.

Rendering: Adam Pardee/STAFF.

We saw it at the sold out Kabuki theater on Post Street in the same Japantown neighborhood where much of the film takes place. It felt like a giant family reunion, with not only much of the cast and crew there, but people who were either in the camps or had family in the camps.

It was the first time I was in a movie theater where it felt like someone had picked up an entire neighborhood and set it down inside.

Full disclosure: My cousin, Renny Madlena, was in the film. He played an FBI agent interrogating a man in the camps. He was, naturally, the most talented and best-looking fake FBI agent in the film, even if his character was kind of mean.

“Kintsukuroi,” which refers to the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mending the broken areas with urushi lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold, silver or platinum, is a good film, especially for an independent effort without name actors made over a period of years. It was obviously a labor of love, which is so rare to see on a big screen in 2024.

It’s good, but even more necessary, it’s an important film. I understood that during the first 30 seconds following the lights coming up and the applause fading, when I looked at my daughter and saw she was a bit wide-eyed.

“I had no idea that happened,” she said.

This was a bit stunning, but not so surprising. A great student who loves history and takes advanced classes at a public school had no idea we rounded up American citizens and put them into internment camps less than a century ago.

That pretty much sums up the U.S. reaction to the shameful travesty that was the internment of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans during the war.

As a nation, we could use more realistic depictions of history, whether we like it or not.

It took the government more than 40 years to formally apologize when, in 1988, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which Ronald Reagan signed into law. It formally apologized to internment victims and gave $20,000 to people still alive who’d been in the camps.

Nice try, Uncle Sam. But you were a bit late.

After we got home, I spoke with my mom, an intelligent and informed lady whose father fought in the Pacific and whose mother was a fountain of WWII knowledge. And she said she didn’t know about the internment camps until she was well into adulthood, like “10 or 20 years ago,” she said.

That’s just mind-blowing. Then again, about 40 percent of the country wants to either remove centuries of slavery from our history books or insultingly refer to slaves as “workers.”

I knew about the internment camps’ existence because I’m a lover of WWII history and am supposed to know things.

But I never considered things like what happened to the homes and businesses of U.S. citizens shuffled off the camps in desolate areas of mostly Midwestern states and non-coastal Western states until a character in the movie laments losing his business because he didn’t pay his taxes because, you know, he was thrown into an internment camp.

The government that still demanded his tax money also gave him and his family 48 hours to get their affairs in order before ripping them away from everything they knew.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt issued executive order 9066, turning the entire West Coast into a military area and various military zones, with military commanders overseeing them.

Those commanders had the authority to exclude civilians from those zones. No ethnic group was specified in the order itself, but curfews for people of Japanese descent — not those descended from other Axis nations Germany or Italy — were initially imposed (Italian Americans were later, briefly, included in the curfews).

Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command — who once blamed a power outage caused by cows on Japanese saboteurs — then issued Public Proclamation No. 4, on March 29, 1942, which began the forced evacuation and detention of Japanese American West Coast residents on 48 hours notice.

Nearly 70,000 of the 112,00 people of Japanese descent who were forced into camps from March to August 1942 were U.S. citizens. They weren’t charged with crimes and had no way to appeal their fate. This country, preoccupied with two theaters of a new world war, allowed it to happen.

There weren’t such blanket internments in Hawaii, which was still cleaning up after Pearl Harbor and where approximately a third of the population was of Japanese descent. Apparently they didn’t have enough loyal white citizens to sustain the then-territory’s workforce.

And though Roosevelt’s initial order made it possible to mistreat people of German and Italian descent, the number of people of European descent incarcerated was estimated to be in the hundreds. The East Coast, particularly New York City, couldn’t function without its Italian Americans, so the West Coast was advised to lay off the Europeans. At least compared to people with Japanese ancestry.

And, lets face it, Japanese people were easier to pick out as the enemy, simply because they didn’t look white. Of course, people of Japanese descent could eventually leave the camps during the war… if they signed up to fight or agreed to leave the U.S.

I’m a big believer in showing instead of telling, of which “Kintsukuroi” did a masterful job. A film with a modest budget and many non-professional actors nevertheless performed wonderfully showing the anguish and unfairness of the Japanese American experience during WWII.

My daughter went to history class the next day and asked why she hasn’t learned about the internment camps. I don’t think she received a satisfactory answer, though her teacher did agree it should be part of the curriculum. She also said she might want to show the film to her classes.

“Kintsukuroi” will be shown at The Sofia in Sacramento at 1:30 p.m. on June 30. It may also have screenings in the East Bay and Los Angeles. It may get some limited release after doing the film festival circuit next year. It’s worth the time.

Follow music critic Tony Hicks at Twitter.com/TonyBaloney1967.