ALBUM REVIEW: Bon Iver enters a fourth season of eclectic spontaneity on ‘i, i’

Though often lauded as a trailblazing hip-hop producer or an indie folk visionary, Justin Vernon is reluctant to take credit for Bon Iver. His songwriting chops are remarkable, but the ingenuity brought to the table by his collaborators gives his work a distinct flavor. That’s apparent on i, i, an album rife with colorful, mystifying arrangements. Looking forward to the autumn, the season of change, Vernon and company take a more introspective approach. What results is an album as intimate as it is forward-thinking. Collaboration, spontaneity and self-awareness make i, i an engrossing ride.

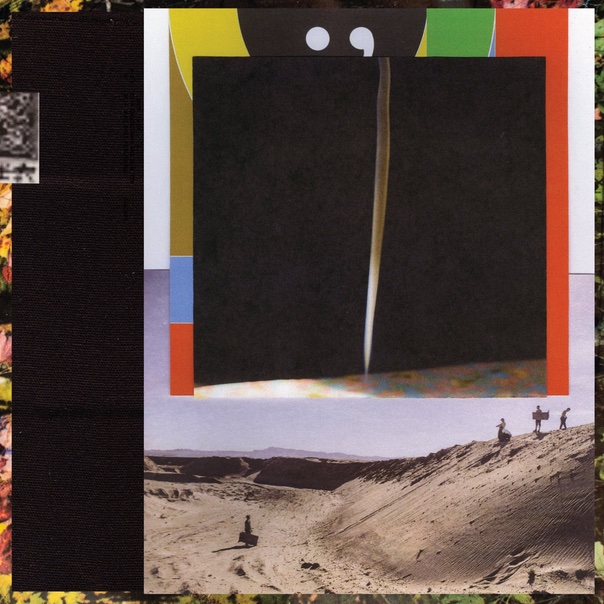

i, i

Bon Iver

Jagjaguwar, Aug. 8

The fact that the half-minute intro “Yi” spent five years in development shows the patient nature of Bon Iver’s songwriting. Vernon was perfectly fine with saving a souped-up phone recording until he found the perfect place for it—as a lead-in for “iMi.”

Combining abstract, vocoded R&B with the robust arrangements of David Axelrod, the song sets a tone of immersive musicality. And yet, it boils down to the immaculate harmonies between Camilla Staveley-Taylor, Velvet Negroni and even James Blake. Vernon’s electro-acoustic production takes full effect, both resonantly woody and deliciously processed. “We” has a similar balance of cloudy beats and swelling instrumentation, but it still dials into a relatable theme of facing reality after a blissfully entitled youth.

As is customary with Bon Iver, improvisation is heavy on i, i. “Holyfields,” “Jelmore” and “Faith” reflect Bon Iver’s propensity for developing off-the-cuff jams to magnificent results. The first cut sees Vernon’s unedited falsetto melodies lasso a synthetic collage, ruminating on the contrast between new opportunities and persisting limitations. In contrast, Vernon credits “Jelmore” co-producers Chris Messina and Brad Cook for inflating the song’s skeletal foundation to a gorgeous Sigur-Rós-esque tapestry of woodwind, string and harmonized vocals.

It’s almost baffling how the massive sound and uplifting themes of “Faith” were originally unplanned. It’s on this coffee-house-ready art-pop number that Vernon comes to terms with his complicated relationship with religion and theism, accepting his personal beliefs and freeing himself from the confines of orthodoxy. The song’s layered melodies and powerful groove make it a standout track both instrumentally and vocally.

Vernon’s confidence in the catchy hooks of “Hey, Ma” is well-founded. His melodies will surely find their way into the end-credits of a handful of indie films. The balance he finds between fluidity and memorability allows modern samples to coincide with complex harmonies and almost conversational vocal phrasing. The same could be said about the Bruce Hornsby collaboration “U (Man Like).” While Hornsby’s piano chops remain central to the tune, even the verse he sings feels in line with Bon Iver’s textured, multifaceted sound. This not only illustrates the timeless quality of Vernon’s vision, but shows his willingness to let others influence his artistic direction.

If nothing else, “Naeem” shows that artists like Yoshi Flower, Post Malone and Joji should be clamoring to work with Bon Iver. While Vernon’s repetitious phrasing bears similarities to those Auto-Tune mumblers, the way the pristine chord progressions develop alongside galloping snare drums and gorgeous brass is engrossing. Similarly, the lo-fi beats and minimal keyboards on “Salem” quickly crescendo to a quasi-orchestral extravaganza. Vernon’s silky voice soars over seamless beat changes, dialing into the bedroom-pop foundation while throwing everything but the kitchen sink into the mix.

Anyone who found the credits of previous Bon Iver albums extensive will be staggered by the cast of contributors to i, i. Where the Bon Iver septet’s input ends and where the contributions of countless other musicians begin quickly blurs, but the album can still break down to folky acoustic guitar on cuts like “Marion.” Multi-instrumentalist and arranger Rob Moose breathes new life into the track with his “Worm Crew” ensemble. This track becomes emblematic of how intuitive collaboration and impromptu songwriting allow Bon Iver’s songs to hit close to home, yet reach beyond anyone’s expectations.

Roughly translating to “The shittiest day in American history,” “Sh’Diah” becomes the contemporary jazz ode to the U.S.’s state of decay. “Keep it rational/ There’s no fountain”—Vernon’s passionate vocal runs plead for the preservation of sanity during the Trump administration before Mike Lewis’s spellbinding solo blasts into the stratosphere. The countless layers of piano, synth and percussive improvisation ultimately settle on a motif of hope.

Indeed, it’s this joy in spite of everything that allows “RABi” to land i, i in placid folk. For all this record’s exploration in sonics and lyrics, it’s clear that it could still stay afloat with Vernon’s voice and rudimentary instrumentation. On this heartfelt closer, Vernon comes full circle to the album’s simultaneous yearning for the past and adaptable calm: “When we were children, we were hell bent/ Or oblivious at least/ But now it comes to mind; we are terrified/ So we run and hide/ For a verified little peace.” Bon Iver’s dichotomy between bodacious alliances and quiet individualism continues to make its artistry almost sentient in its infectious beauty.

Follow editor Max Heilman at Twitter.com/madmaxx1995 and Instagram.com/maxlikessound.