SF Ballet brings back ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ for the first time in three decades

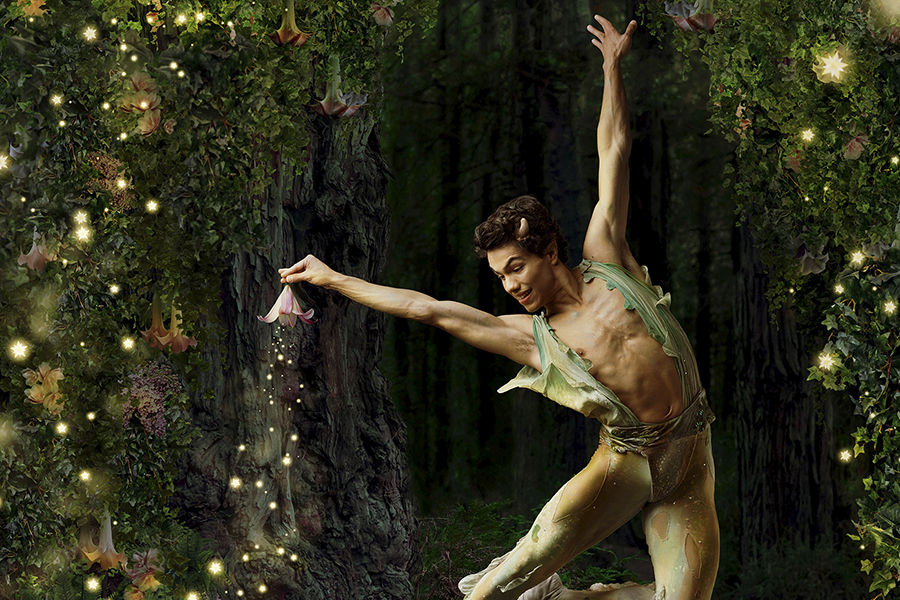

SF Ballet dancer Esteban Hernandez as Puck in Balanchine’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream.’ Rendering courtesy of Erik Tomasson and Sky Alsgaard. Rehearsal photos: Adam Pardee/STAFF.

UPDATE: By order of San Francisco Mayor London Breed, all performances at the War Memorial Opera House have been cancelled through the end of the summer as precaution to limit the spread of Coronavirus. The SF Ballet has added “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” to its 2021 season.

SAN FRANCISCO — Two couples take turns chasing one another across the fourth-floor rehearsal studio of the San Francisco Ballet headquarters on Franklin Street, just across the street from the majestic War Memorial Opera House.

San Francisco Ballet

“A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

Part of the 2021 Digital Season

The dancers are playing the roles of the “lovers” in George Balanchine’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” a faithful recreation of the William Shakespeare comedy. In the ballet, once fairy servant Puck rains mischief down upon four humans with a magical flower pierced by Cupid’s arrow, a love quadrangle leads to obsession and plenty of temporarily broken hearts.

The ballet debuted in 1962 but hasn’t been staged by SF Ballet for 34 years. Balanchine, who founded the New York City Ballet, died in 1983. To stage a production authentic to his vision, SF Ballet sought the assistance of the George Balanchine Trust, and this is why trust répétiteur Sandra Jennings, the “stager,” is calling the shots, stopping the rehearsal at least once a minute with three claps that could pass for applause.

Stager Sandra Jennings (middle) works with dancers Daniel Deivison-Oliveira (left) and Hansuke Yamamoto (right).

“This is too fast; too fast,” Jennings says to one couple as the woman pursues a man across the studio floor while he acts as though he’s pushing her away.

The production debuts for a 10-day run in a little over a week. Jennings knows the choreography front to back and travels the world, teaching it to other companies from Paris to St. Petersburg, Boston and Philadelphia in recent years. But now she still sees minor missteps. As she stops the action, she walks from her chair to the dancers, molding them physically like clay. She changes their posture, location on the floor and even the directions in which their arms point.

“Which Pucks do I have?” Jennings asks the large room. There are about two dozen dancers in tights and skirts, or sweats, lining the perimeter. In fact, there are three Pucks present. A fourth, SF Ballet Principal Dancer Esteban Hernandez, is there to learn the part of fairy king Oberon, whose quarrel against his wife, Queen Titania, kickstarts the drama in the story.

In fact, there are five separate casts for SF Ballet’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Each dancer in each cast must learn his and her movements perfectly. Dancers from the other casts are watching from across the floor and some are mimicking the same motions, though Jennings gives her attention to just one group at a time.

L to R: Hansuke Yamamoto and Ellen Rose Hummel rehearse while Ulrik Birkkjaer and Elizabeth Powell match the same scene

In the scene being reenacted over and over, Puck prances around with a magic flower that can make you fall in love with the first person you see. He wreaks havoc in the lives of four young lovers from Athens.

Hermia is engaged to Lysander, but Demetrius loves Hermia, and Helena loves Demetrius. It only gets more confusing from there. Oberon and Titania get thrown into the mix themselves when Puck douses her with the magic flower, turns a wandering musician into a donkey and she promptly falls in love with the him.

But what this means is that the dancers have to communicate many of the complicated nuances of the story through their movements. The goal is to distill the plot of an entire five-act play into, essentially, a one-act ballet (there’s a shorter second act) that explains the story to everyone, even if they’re not a devotee of Shakespeare.

“It’s not only about the steps, it’s more about acting; it’s more about personality,” Argentine dancer Lucas Erni, who plays Puck in one of the casts, says about his role a few days following this rehearsal. “Ballet for me is not just about technique, and this is the perfect ballet to show it.”

In a separate call, Jennings explains that Balanchine wrote the choreography for the ballet specifically for the very purpose of conferring the action and plot of Shakespeare’s play to anyone.

Elizabeth Mateer midair while (L to R) Lucas Erni, Esteban Hernandez, Daniel Deivison-Oliveira and Diego Cruz look on.

“The gestures are extremely important to tell the story,” she says. “With ballet, sometimes because we move so quickly, if the gestures aren’t right, the audience isn’t going to understand, especially when you’re in a big opera house. You have to be specific. … You want each of the dancers to bring themselves to the character … but they have to stay within the boundaries of the choreography.”

Dancer Elizabeth Mateer, who plays Helena in one of the casts, later explains how the introduction of the lovers is played for laughs because of the tight choreography. In the scene, the four reject each other in quick succession.

“A simple swish of the arm across your body indicates, ‘No, I don’t want you.’ It happens four times in a row, and I think if the timing is executed properly and we execute it similarly, it’s very funny,” Mateer says.

Back at rehearsal, the dancers try to take in these minute corrections carefully. There’s a quick sequence where a ballerina performs an arabesque, followed by a twirl from a male counterpart, who must do so while holding a very specific pose. “It’s hard,” he says, grimacing. A classical pianist, who’s performing German composer Felix Mendelssohn’s score at the rehearsal, also receives feedback from Jennings, who at one point tells him not to slow down, which his sheet music had instructed him to do.

“Balanchine didn’t want it slowed down,” Jennings declares.

Mateer, who’s in the second group to rehearse, watches the action carefully even though the former Pennsylvania Ballet dancer has played just about every role in this ballet earlier in her career. She likes to get into the head of each character she portrays.

“[Helena is] really sad. She’s introduced to the audience simply walking across the stage with a heavy heart,” she says. “Her love, Demetrius, doesn’t return her love. So rather than pumping myself up I like to psych myself down and avoid having too much adrenaline. Her relationship with Demetrius is very much tempestuous. So I like to think how I’d feel if my love rejected me.”

The lovers continue to run through this 90-second sequence over and over—not just the dance steps but the story they convey. Puck lulls the men to sleep with his magic flower, and they practice different ways to slump to the ground. Both men fall in love with Helena.

L to R: Elizabeth Mateer, Hansuke Yamamoto and Ellen Rose Hummel work on a scene while other dancers look on.

The lovers quarrel. The women fall to their knees once, twice, three times. The men get pushed away. Not knowing what has happened, Hermia is heartbroken. And so the dancers take turns pursuing and rejecting each other.

It may seem that the female characters are being used, which in the #MeToo era is counterintuitive in art. Jennings says she’s considered that, but believes Balanchine’s original vision of the ballet was forward-thinking. In the original story, for example, one of the men almost kicks a woman. This was never part of the ballet.

“In this particular ballet, the women are very strong characters,” Jennings says. “It’s such a human story. You fall in love with someone who’s in love with someone else, and you do stupid things to try to get their attention. … The actions depicted are not sexual in nature. Some of the guys can be forceful, and we talked about that, but when they’re too gentle, it doesn’t work. It’s slapstick a little bit … like vaudeville.”

Much of the comedy comes from Puck, who’s responsible for plenty of mischief. Jennings allows each dancer who holds the role to imbue it with his own personality.

“He plays a lot and loves to get in trouble,” says Erni, who grew up outside Buenos Aires and got his start dancing tango, jazz and salsa before starting in ballet at 14. “He makes some mistakes [and] keeps enjoying those moments. … The role is unique because Puck interacts with almost all the key characters on the stage.”

Other highlights of the ballet include dancing roles for 24 children, most of whom accompany King Oberon as various insects. Jennings describes the roles as more involved and challenging than in other ballets, because Balanchine loved getting children involved in the ballet. To SF Ballet Principal Dancer Mathilde Froustey, it also evokes the feelings of childhood; and she compares it to a summer version of “The Nutcracker.” It also has some more challenging steps for the principal dancers, such as the role of divertissement section, which includes many pirouettes and technical steps.

“It’s not one story—it’s a lot of different stories,” said Froustey, who will perform the role of Helena on Friday with other principal dancers on opening night. “In most story ballets it’s only one or two principal dancers on stage. In ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream,’ you get to see six, seven, eight principal dancers on stage, at the same time. It’s really unique.”

- L to R: Benjamin Freemantle and Dores André practice a scene while Daniel Deivison-Oliveira, Ulrik Birkkjaer and Elizabeth Powell look on.

- L to R: Hansuke Yamamoto, Elizabeth Mateer and Ellen Rose Hummel work out a scene while other dancers look on.

- Benjamin Freemantle (L) and Dores André rehearse a scene.

- Elizabeth Mateer (L) and Hansuke Yamamoto rehearse a scene.

- L to R: Benjamin Freemantle and Dores André rehearse a scene while Hansuke Yamamoto and Ellen Rose Hummel mirror the movement.

- L to R: Sandra Jennings, Hansuke Yamamoto, Elizabeth Mateer and Ellen Rose Hummel work out a scene.

- L to R: Elizabeth Powell, Ulrik Birkkjaer, Dores André and Benjamin Freemantle rehearse a scene.

- Stager Sandra Jennings (R) goes over a scene with dancers Benjamin Freemantle and Dores Andre.

- L to R: Mathilde Froustey, Dores Andre, Ulrik Birkkjaer and Elizabeth Powell watch as a scene is rehearsed.

- Rehearsal with dancers and artistic staff.

Follow editor Roman Gokhman at Twitter.com/RomiTheWriter. Follow photographer Adam Pardee at Instagram.com/adampardeephoto.