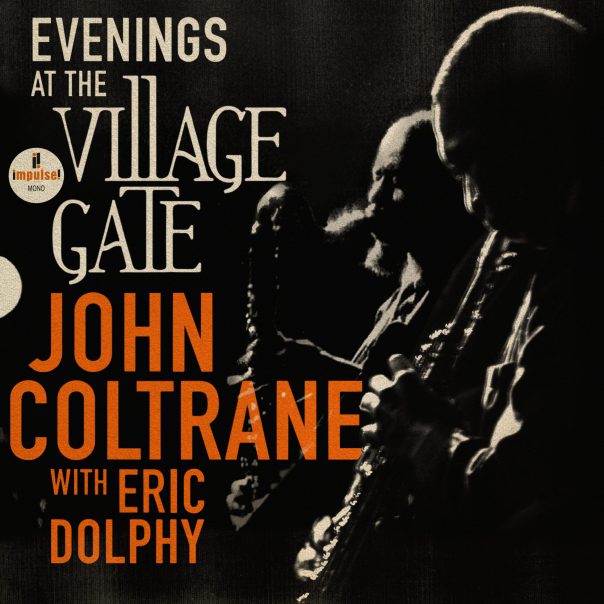

REVIEW: John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy unearthed on ‘Evenings at the Village Gate’

John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy, “At the Village Gate.”

John Coltrane is synonymous with artists who, through discipline and hard work, free themselves from the musical conventions of their era and set a new course for the freeing sounds they hear in their head. The saxophone player’s sound evolved from graceful and fluid renditions of classic ballads to intense, frenetic and chaotic skronking that laid much of the groundwork for what would eventually become free jazz. One of the tragedies of jazz is that saxophonist Eric Dolphy isn’t as well known as Coltrane. While the pair performed and recorded together in the 1960s, there aren’t a ton of recordings. A new live album, Evenings at the Village Gate, captures the duo playing live in 1961.

Evenings at the Village Gate

John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy

Impulse!, July 14

7/10

Get the album on Amazon Music.

The performance is an important one for jazz-heads, capturing Coltrane emerging as a powerful band leader, just a year after playing in Miles Davis’ band. The performance is also noteworthy for the incredible interplay between Dolphy and Coltrane. While Coltrane is known for the power and intensity of his playing, Dolphy is part acrobat, part race car driver, swinging and swerving between unpredictable musical choices with the preternatural calm of gymnast Simone Biles in the midst of a double backflip.

Dolphy begins the album’s opener and standard for Coltrane’s set at the time, “My Favorite Things,” on the flute. The band’s rhythm section of drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Reggie Workman lay down a groove with spare piano chords from McCoy Tyner. The song’s vocal melody becomes a kind of Christmas tree that Coltrane and Dolphy decorate with flurries of musical ornamentation. Fluttering flute and gentle horns create space around the groove with tasteful restraint.

But as the 15-minute performance evolves, it’s as if the two are contacted by inter-dimensional beings and begin trying to communicate. Dolphy plays long notes on the flute that growl and gurgle with overtones and harmonic content usually found in a Jimi Hendrix feedback solo. Coltrane’s staccato rhythms imbue a single note with near endless complexity as the drone takes on a punk rock intensity.

Each of the five songs on the album contains a similar transformation. Where some will hear only a kind of destructive savagery as the band rips up their musical rulebooks, keener listeners will hear the space being made for something entirely new, a music that relies entirely on the fire burning within the musician, a music that turns every chord and melody, not to mention every moment and memory, into fuel for that fire. And the goal becomes to show the audience how brightly you burn.

Evenings at the Village Gate probably hasn’t seen the light of day previously because the sound quality leaves something to be desired. This live recording was likely made with only a pair of microphones, and as a result, it’s difficult to hear much of the sonic detail. It’s particularly difficult to hear detail in the bass and piano, while the drums are a bit loud in the mix. If you’re familiar with these players and aware of the historical importance of these performances, this album is a valuable document that offers up some astounding playing. If you’re a casual fan, check out the pair on Coltrane’s 1963 album, Impressions.

Follow writer David Gill at Twitter.com/saxum_paternus.