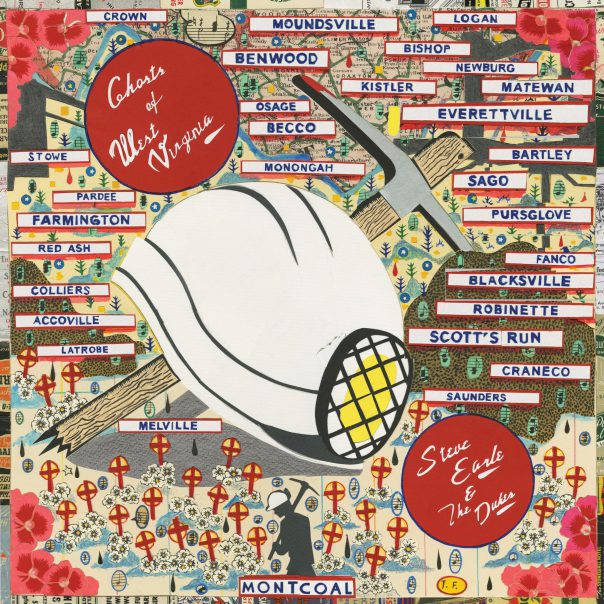

ALBUM REVIEW: Steve Earle and the Dukes mine hard times on ‘Ghosts of West Virginia’

In the heart of Appalachia, that rich musical territory, lies West Virginia, a place known for beautiful mountains and luckless coal mining ballads. The latest record from Steve Earle and the Dukes ventures into the state’s musical and economic heritage. On Ghosts of West Virginia, Earle explores the hardships of the coal mining lifestyle and visits a range of American folk and rock styles. The record that emerges is gritty and persistent, with an undertone of defeated will.

Ghosts of West Virginia

Steve Earle and The Dukes

New West Records, May 22

The songs on Ghosts Of West Virginia were written to accompany Coal Country, a play about the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster that occurred in West Virginia in April 2010. As a result of a coal-dust explosion 1,000 feet underground, 29 miners were killed. The play, written by Jessica Blank and Eric Jensen, was created from conversations with the surviving miners and the families of those who died. Earle himself performed songs from the album onstage with the actors at its opening in March. The production has since been put on hold due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Earle’s downtrodden lyrics and the astute musicianship of the Dukes inhabit the subject matter admirably. The songs never come across as condescending or tacky, helped along by the loose jamming style of the band. “Union, God and Country” is a bona fide hillbilly romp, beefed up with the Dukes’ thick sound. Earle establishes the setting, calling out West Virginia by name, as he crafts an homage of sorts. “My daddy was a miner/ My daddy’s daddy too/ Union, God and country is all they ever knew,” he sings straightforwardly.

Crisp banjo heralds the driving “Devil Put The Coal In The Ground,” a tough tune that simultaneously extolls and damns the positioning of coal. “Lord giveth and he taketh away,” Earle growls before emitting a raspy cough, indicative of conditions in the mine. An electric guitar solo pierces the mix, giving the song a hard edge. The score churns with thumping drums, foot tapping rhythms and a catchy rhyme scheme. Taken for granted is the idea that the mineral must be attained. “You’ll be long gone/ Dead in the way/ That’ll be a dollar someday,” Earle rasps, envisioning lucrative deposits abandoned by Satan in the depths of the earth.

The album features meaty production, courtesy of audio engineer Ray Kennedy. Each instrument, including Earle’s voice, sounds loud and upfront. Energetic instrumental performances sizzle along with a clarity that captures the nuance and subtlety of live performance. The whole record sounds slightly overdriven, hot banjo and fiddle vying for primacy in the tumult. Recording for Ghosts of West Virginia took place at New York’s celebrated Electric Lady Studios, of Jimi Hendrix fame.

Interestingly, the recording merges bombastic modern rock production with Earle’s raw and faithful take on Appalachian folk music. Early 20th century recordings in the style are marked by their dated, lo-fi sound, but Earle’s band sounds brash and vivid here. This might not make a distinction if Earle’s songwriting were less on point. His convincing lyrics, authentically rustic chord changes and ragged dusty voice do justice to the subject matter and the region. Earle nails the spirit of the coal miner’s dilemma. Although the songs on Ghosts of West Virginia are originals, he might just as well have discovered them in a decrepit old song tome from Monongah.

Grit and grime line the walls on the fiddle-driven “Black Lung.” Appropriately, the song showcases the ragged capacity of Earle’s voice. Woozy, seesawing fiddle sustains a theme of determination and fatalism. Traditional instruments gets their volume cranked, and musically the song is packed with little intricacies.

Album centerpiece “It’s About Blood” rocks with swagger and snare rolls. Bright, rich guitar and wailing fiddle underpin the record’s most potent pronouncement. “It’s about muscle/ It’s about bone,” Earle declares, with a haggard drawl. The song would be equally at home in the spaciousness of a saloon or as the soundtrack to a commercial for a Chevy pickup. When Earle calls out the names of Upper Big Branch’s deceased, however, the context of the song becomes irrevocably clear and somber.

Quieter moments crop up, such as the gentle lullaby “Time Is Never On Our Side” and meandering ballad “If I Could See Your Face Again.” The a capella “Heaven Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” deceivingly complex in its structure, carries a certain gravitas. Lyrical phrases about hard times play musical chairs with choral harmonies. Part hymn and part chain gang work song, it stands in stark contrast to the driving hootenannies and tobacco-stained melodies that populate much of the disc.

Earle’s invocation of Appalachian and American mythologies, such as the ubiquitous John Henry, create a bedrock of old-timey austerity. Considering the disaster that inspired the album happened relatively recently, the rootsy direction seems to be Earle’s way of placing the subject matter in the tradition of coal-country balladry. Though a valediction for the miners who lost their lives, and the faded prosperity of West Virginia’s coal industry, Ghosts Of West Virginia sounds resonantly present and alive.

Follow writer Alexander Baechle at Instagram.com/writheinsmoke.