Q&A: Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark shine light on Western excess

Courtesy: Mark McNulty

Think of Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s new album, The Punishment of Luxury, as a broad look at a few of the deadly sins—particularly envy, greed and gluttony—and the band’s attempt to reconcile them.

Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark

GGOOLLDD

8:30 p.m., Tuesday, March 27

The Regency Ballroom

Tickets: $40-$50.

Kraftwerk-inspired track “Isotype” delves into the replacement of written language with emojis. The album-opening title track is about having more than we could ever need but being blinded by the constant urge to acquire the next big thing.

Synthpop pioneers Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark also have a song called “La Mitrailleuse,” which translates from French as “Machine Gun,” and consists primarily of vocals atop a layer of automatic weapon fire that may elicit intense reactions from some. The song, as it turns out, was inspired not by the unceasing string of mass shootings in the U.S., but by the early mechanization of warfare.

But OMD vocalist Andy McCluskey, who, with keyboardist Paul Humphreys, helped bring electronica to the mainstream with hits like “Enola Gay” and “If You Leave” in the early ‘80s, acknowledged the song’s parallels with what is happening in America right now.

“The song is inspired by a [1891] painting of WWI French machine gunners,” McCluskey wrote in an email to RIFF last week. “We have always been fascinated [and] horrified by the moral questions surrounding warfare and the interface between humans and machinery.

“Obviously, there is a repeating sad theme in the USA of mass killings using automated rifles,” he wrote. “This isn’t going away any time soon because there still seems insufficient appetite among lawmakers in the USA to attempt much meaningful legislation due to so many politicians taking funding from vested interests, and understanding that many of their constituents in certain States still hold firm to the right to bear arms.”

Yet this album is not doom and gloom, presenting hope on tracks like “The View from Here,” confronting life-changing events on “What Have We Done,” which Humphreys wrote following the death of his pup, and being brave enough to show vulnerability on “Robot Man.”

McCluskey and Humphreys recently celebrated their fourth decade of making music together. The Punishment Of Luxury, which was released last September, is their 13th studio album, following in the footsteps of 2013’s English Electric. OMD will bring its U.S. tour to San Francisco later this month.

Are there still things the two of you are discovering about each other after knowing each other for 40 years? Things like tastes in music or production styles, the ways in which you like to work, or the directions you want to pursue? Or does this band have such longevity because you know each other so well?

Andy McCluskey: We certainly know each other very well by now! It’s [been] 50 years since we met at school, and 42 years since we started making music together. The most important thing that we have learned and respect is that it is our differences that usually make us a stronger combination. Knowing that the other can do things that we are less capable of, therefore trusting that between the two of us, we can get a better result! As an example, musically, I have a ruthless overview when it comes to editing and arranging, but Paul is by far the more objective and technical when it comes to mixing.

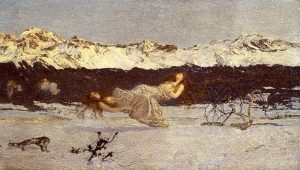

The title of your most recent album comes from a 19th century Geovanni Segantini painting; how did you discover this painting, and why did it play such a crucial role in your creation process?

McCluskey: We appropriated the title but not the meaning from the Segantini painting in Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery that I have known since my teen years, [including another Segantini work called] “The Bad Mothers,” floating in an Alpine purgatory because they wanted more than a life in the kitchen, nursery or bedroom! Our take on the title is that most people in the Western world are materially better off than ever before, but we are unhappy because we have been brainwashed into believing that we are unworthy of love or self-respect unless we own the latest product being offered to us! It is a cruel and twisted delusion that we have been sold by the marketing men.

Who are you singing about on “Robot Man?”

McCluskey: The “Robot Man” is me. Or rather, I hope that it was me. The song is an attempt to state my aim to take off the armor that I have created to protect myself and be self-assured enough to allow for some pain and shame in an attempt to be more honest and open. Musically, it is also a small homage to the early minimal synth music that we loved, especially “Warm Leatherette,” by The Normal.

Listening to “What Have We Done,” I could tell the song, on which Paul sings lead for the first time in 30 years, was a personal story and not necessarily a bigger message about the ills of society in the Brexit and Trump era. Then I learned it was about the death of Paul’s pup. How were you able to communicate your feelings?

Paul Humphreys: Now, it was indeed inspired and written on the day that I had to put my doggie down, but “What Have We Done” is more of a personal song about life, love and loss, about putting full stops at the end of an era. It’s about facing and confronting life-changing decisions and situations that we all have to face at some point in our lives, and then having to live and deal with the resulting and inescapable consequences of our choices. Andy and I are very politically aware but try not to be too overt or preachy in our songs. But like other world political “earthquake” events, Brexit is as big of a “What Have We Done” moment the U.K. has had to face in my lifetime. I personally believe it will be an unmitigated social and economic disaster, but very happy to be proven wrong!

In the 1980s everyone was signing huge record deals but signing away all the rights to their songs. Right now artists are better at keeping the rights to their music, but the industry is much less receptive to the type of music that doesn’t move millions of units, and stuff on the radio is more homogenized than ever. You’ve been a part of both times. Which is better and why; and what makes the other era worse?

McCluskey: The music industry now is a very different model to the one that we signed up to. We accepted fairly terrible royalty rates that no one would tolerate these days. At the end of the 1980s we had sold 10 million albums [and] 20 million singles, and owed our record company a £1 million—not because we had bought castles and yachts, but because our royalty rates, even on songs that we had written ourselves, were so low! Since digital arrived, record companies have struggled to make the big profits that they used to. Therefore, they are much more reluctant to invest in anything that could be considered a chance. Thus, we have music in the mainstream that is very homogenized and predictable. A band called Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark would never get a major record deal now! Only a handful of massive artists make money from music sales. Some, like ourselves, survive through touring and maximizing the support of a wonderful existing fan base, but for many others it is now never going to be a “job” that pays the bills. I know which era I prefer!

You waited four years between albums last time. Should fans expect a similar break, or have you been writing all this time?

McCluskey: We didn’t wait four years. We were working on it! After almost 40 years making and releasing music as OMD, it is hard to continue to find new ideas and inspiration. … The only reason we make a recording is because we feel we have something relevant to say and of sufficient musical quality [and] it will take as long as it takes to prepare something good enough for release. We could write 10 songs in 10 days, but they wouldn’t be good enough! It’s that simple! We refuse to release an album just to have a new T-shirt logo and excuse to tour! We like to think that that is why our new albums have been very strong.

Follow Roman Gokhman at Twitter.com/RomiTheWriter.