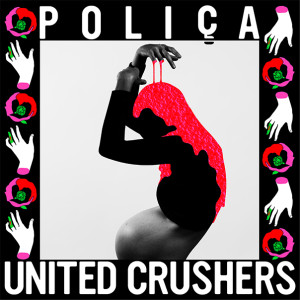

Poliça looking for hope in the trash pile with ‘United Crushers’

Courtesy: Jonathan Weiner

At first, Channy Leaneagh, vocal and creative leader of electronic rock and pop quartet Poliça, wavers on the thought. Does the Minneapolis native now officially write for electronic music? Or is she still the folky singer-songwriter she was when she was younger?

“I don’t know. I don’t know,” she repeats, frozen on the thought. “When I get to customs and they ask me, I just say, ‘I’m a singer.’”

But the socially conscious musician recovers less than five minutes later while talking about her home city’s active Black Lives Matter movement, the police shooting death of Philando Castile in a Minneapolis suburb, her band’s strong political beliefs, which they impart on their third album, United Crushers, and Leaneagh’s definition of personal success.

Poliça

Thursday, The Independent

Doors: 8:30; show: 9 p.m.

$30, 21+

Friday, Outside Lands

3:40 to 4:30 p.m., Land’s End stage

Sold out

“We’ll go to that first question, real quick— I like to always consider myself a folk singer,” Leaneagh says. “I like the idea of success being continuing to be able to make music. Because that’s something I never want to take for granted. The opportunity to continue to sing for people and to make music with my friends … are kind of the two things that I love most about what I do.

“I’m also happy that I get to speak my mind,” said the resident of the same state that gave us Bob Dylan. “The great folk singers that I’ve always looked up to are people that have things to say, that challenge people and inspire people, and I like that about that title.”

Poliça released United Crushers in March, long before Black Lives Matter mourned Castile. But the issues of social justice, grief and heartache are even more relevant now. The album itself is named for Minneapolis graffiti artists, now mostly disbanded or underground, who spray-painted the United Crushers tag in prominent places.

But to Leaneagh, those two words also mean people uniting to crush hate, poverty and other dark forces.

“That is kind of the theme over the record,” she says. “Even the song ‘Lately,’ which is a straight-up love song. I always write a lot about my own isolation and being lonely. This record is trying to encourage the idea of uniting together in love, as people, (and change) things that need to be changed.”

The title follows a trend for Poliça, whose debut, whose sophomore album, 2013’s Shulamith, was named for feminist Shulamith Firestone.

Among the social just themes are the war on drugs and the future that is left for the youth of today. The song “Wedding,” and its accompanying video, are especially moving, with images of military and police shows of force interlaced with a faux-Sesame Street TV show where puppets and kids learn how to behave around police, make gas masks, and vocabulary that most of their white peers will never have to hear.

While the song itself is about the marriage of the drug trade and police militarization, the video has even more dimensions. It stemmed from a conversation Leaneagh had with frequent collaborator and director Isaac Gale and was based on an actual episode where kids made crayons during arts and crafts.

“We have lost so many black men here to police violence and … how do you talk to your kids about this stuff when they are kids of color, their dads or their moms are black, or their friends’ moms, and there’s this fear over our community, over our city?” she says. “Kids are going to hear that. How do you teach your kids in a way that’s not fairies and flowers, but it’s also not too dark, and it doesn’t kill their soul and their spirit? How do you empower without making people afraid?”

Shows like Sesame Street and Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood taught children real life lessons. In a way, the video was not much of a stretch. Leaneagh and her band mates, Chris Bierden (bass/vocals), Drew Christopherson and Ben Ivascu (drums), recruited their friends’ children to act in the video. All of them had already been taught about the Black Lives Matter movement and what the video portrayed. Many of them have already participated in numerous marches and protests.

Castile was shot and killed July 6, five months after the album’s release. It’s a dark stain on the state of Minnesota, live-streamed and shown to the world, that Leaneagh hopes is never forgotten.

“(Minneapolis) often gets written up in different papers as being a really great state—it’s not a great state,” she says. “It’s not a good city for black people. It’s not a good city for children. I hope Minneapolis is remembered for that and Minneapolis works really hard to change the reputation. I grew up in Minneapolis, and I’m really ashamed … in my city.”

While the album looks at issues with more world significance, it’s also more hopeful than Shulamith and 2011 debut Give You the Ghost. Songs like “Fish on the Griddle” show a careful dichotomy between downcast and uplifting. That song, as well as “Baby Sucks,” call out a former band manager who Leaneagh says tried to manipulate Poliça and ruin the band in numerous ways during their run on their second album.

The central album theme, as is the message of both those songs, is about reclaiming hope.

“Life is filled with a lot of pain, whether that’s just heartbreak or cops shooting people or poison water, but you can choose (whether) or not choose to suffer,” she says. “So, there’s a sense on this record of being in love, being in love with the band that I play with, and trying to find hope. It’s a dark time, and I’m not someone that likes to make music that lets you forget about everything. We’re not a pop band. There’s time for that, but I tend to want to make people feel power in their sadness or hope in their darkness. That’s what music does for me.”

Leaneagh has several reasons to be hopeful and optimistic. Between album cycles, she married longtime collaborator Ryan Olson, who has produced and co-written on all three Poliça albums and helped her start the band in 2011.

Last October, the two welcomed a son. (She has a 7-year-old daughter with musician ex-husband Alexei Casselle). Being a new parent again refocused her vision and concerns about the direction of the country and the world.

Channy Leaneagh on her marriage to producer Ryan Olson, playing festivals and Bay Area memories

How does your marriage to Ryan, the band’s producer, affect the music you make?

“The main thing that always influences a Poliça record is (my) and Ryan’s relationship and conversations. We’re married now, but we weren’t for a long time, and we weren’t even together for a long time. First record, and second, kind of conversations to him and trying to figure out what started as a friendship; the strong connection we have. I used to always write these letters to him and even when I was thinking about the world and things that I’m upset about and angry about, he’s my best friend.”

Is playing festivals fun for you, or is it just a part of the job?

“Festivals are fun. They can be challenging. You never know what it’s going to be like there. If it’s going to rain of if there’s going to be a good sound system. Everyone’s usually in a really good mood, and it feels like camping. I just got done with a month of European festivals. Also, as an artist, I don’t often get to see so many other bands because I’m busy. It’s a chance for me to feed off of other acts.”

Do you have any meaningful memories from the Bay Area?

“I have so many memories of San Francisco. Ryan took me out for our first Korean barbecue there. I’m a vegetarian, but I remember that experience really well. I will not talk your ear off about this, but San Francisco has always been very good to us, and we’ve played there a lot, and we always fill it out. We often come there from L.A., and we don’t always have that good of an experience in L.A., playing shows. Then we get to San Francisco and the crowd is really lively and fun, and they’re very good to us there. So, I’m very grateful to places like the Fillmore and the Independent.”

“Once you have a kid, you start seeing the world through your kid’s eyes and feeling how they and other kids see the world,” she says. “It just becomes more urgent. You want the streets that your kids play on to be safe. You want them to be able to have enough food to eat. You want kids to feel safe when they go to bed and they wake up in the morning. You start seeing this innocence, how much they depend on you, and how some kids don’t have someone to depend on. It makes you sad. You want things to be better.”

Olson and their son have joined Poliça on tour this year, travelling by van from country to country, filling up the tot’s passport book. Sometimes, her brother joined the band as well, to help out. The band hasn’t once complained, and as a result she has gotten quality bonding time.

Her daughter also toured with her when she was younger, but now attends a demanding Chinese immersion school at home, and has too much fun to skip class. To make it up to her, later this summer the two will return on a mini vacation through Big Sur, Half Moon Bay and Yosemite.

The typically private singer has opened up more with United Crushers. The album cover is a stylized photograph showing (among other things) her baby bump. She has balanced her private and public lives by taking personal incubation time with her family, and expelling her creative energy on-stage.

“I don’t know if I do it very well, but to me it’s something that I take really seriously,” she says. “I pour myself into both. I just divide them up.”

A similar separation approach was made to record United Crushers. Leaneagh and Olson wrote from 2013 to 2015. Once they completed “Summer Please,” the album’s mood and tone were set, and Poliça had its direction. The song begins darkly but experiences an uplift in the middle and concludes on an exclamation point.

The band rehearsed the new material relentlessly before decamping to Sonic Ranch studio in Tornillo, Texas, close to the Mexico border. While the previous albums were made in DIY fashion at home. This time the band wanted to step out of that comfort zone and pushing themselves to make something more creative and original.

But studios in the industry’s centers were quickly ruled out. They ended up at Sonic Ranch, on an expanse of pecan trees thanks to recommendations from Olson, Beirden and friend Sean Tillman of Har Mar Superstar.

“We’re not people that like to go record surrounded by the industry,” she says. “That is disgusting to us; New York and L.A. (And) we wanted to just get away from anything we knew, (and) familiar.”

The result was a collected work that was more pointed and direct, with vocals that largely abandoned vocal distortion and murkiness, while retaining enough elements of electronica and trance to keep older fans interested.

Follow Roman Gokhman at Twitter.com/RomiTheWriter and RomiTheWriter.Tumblr.com.