Obituary: Fairness demands remembering Phil Spector for who he was

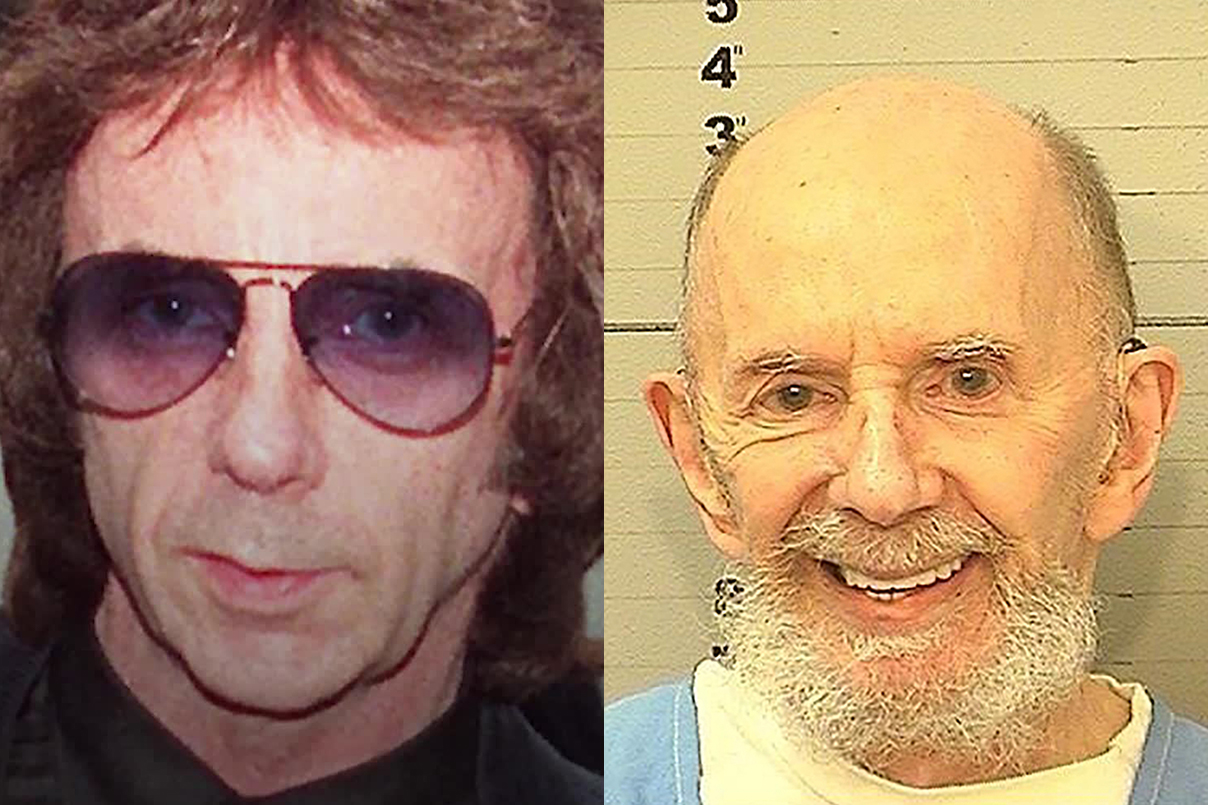

Phil Spector photographed in the 1970s, and a recent booking photo.

I heard Phil Spector died and immediately thought of the end of “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.”

That’s happened every time I’ve heard Phil Spector’s name since 2003, when he killed Lana Clarkson, the actress who played the wife of freakishly dry Mr. Vargas’ wife at the end of the 1982 film.

Spector died Saturday of COVID-19 in a California prison at the age of 81, which was the second thing that struck me. He was, what … 30 or 31 when three of the Beatles turned him loose with the epic responsibility of finishing their swan song (at least release-wise), “Let It Be?”

Even more than five decades later, that sounds incredible. Plenty of widely successful people were barely beginning life at that age. The reflective juxtaposition is still amazing, no doubt the product of some sort of genius not easily understood.

Then, because a friend and I discussed the Buffalo Bills finally winning their first playoff game since 1995 on Saturday, I thought of O.J. Simpson. He popped up as a game-changing talent in his time with the Bills, before becoming better known as a crazed, knife-wielding (alleged) murderer.

What should either be remembered for: their astounding careers or their violent insanity?

Both. One can’t be fairly mentioned without the other, even in 2021, when the accuracy of narratives have never been more dependent on who’s doing the telling. Just in the few hours after Spector’s death was announced, I saw plenty of headlines mentioning one without the other.

Guilt is a frequent companion to recognition of a murderer’s brilliance.

That Spector was an artistic genius shouldn’t be in doubt to anyone. His “Wall of Sound” was the most aptly named production technique in rock and roll history. It wasn’t about big volume; the sound came in layers and waves of instrumentation making previous pop music sound like it was played underwater or at a distance; big sound without noisy volume. He used string sections along with various studio tricks to create a rich unusually dense and rich soundscapes that cut through on small portable radios and sounded absolutely immense on high-end audio gear. Phil Spector was the first to approach production like a member of the band, his soundboard as important as any instrument on any record.

Spector’s approach to production is probably best captured on the Righteous Brothers’ hit “You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling.” Rather than going for stripped-down sincerity, he was known for his tasteful application of smaltz. The song’s slowly rising tension and burning intensity is epic and cinematic, getting much of its power from the powerful use of strings and use of cavernous reverb.

Spector applied his hallmark production strategies on everything. Even Lennon’s simple acoustic ballad “Across the Universe,” which the producer festooned with string sections and Lennon’s multi-tracked vocals.

Nobody delivered production of simple pop and rock and roll to human ears the way of Spector. He was at least partially responsible—through acts like The Ronettes, The Crystals, Ike & Tina Turner, The Righteous Brothers, and on and on—for a tectonic shift making later groundbreaking records from The Beach Boys and The Beatles possible. He produced the best solo work from Lennon and George Harrison. He helped make America’s greatest punk band, the Ramones, sound perfectly, powerfully and wonderfully retro.

Spector was also an abusive, moody, dark, egotistical taskmaster who carried guns in the studio and shot Clarkson to death.

For some, that’s all they need to know. It’s not so simple for everyone. Separating the art from the artist has always been problematic. Sometimes it’s difficult to listen to a cross-section of great artists without being reminded of crime and other dark and twisted connection. It’s not easy loving the music of Richard Wagner without acknowledging the baggage of his anti-Semitic views and that Adolph Hitler was fanatical in his devotion. It’s difficult to laugh at Michael Richards on “Seinfeld” reruns without remembering his racist tirade at a comedy club in 2006. Sid Vicious killed Nancy Spungen, though he overdosed and died before he could be convicted.

Honesty should demand we recognize Phil Spector as a music genius. He was also a psychological predator and a killer. Mentioning one without the other is dishonest and unfair, both of which we could use less of in our storytelling.

Writer David Gill contributed to this report. Follow music critic Tony Hicks at Twitter.com/TonyBaloney1967.