Professor Music: This column is Devolving

In January of 1977 Devo’s guitarist, Bob Casale, came up with a riff. By the end of the afternoon the band had morphed it into their version of the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” They weren’t covering the song, they were, in their words, “correcting it.”

David Gill. Julia Kovaleva/Staff.

Two hundred years before Devo corrected “Satisfaction,” scientists were developing a new theory of “devolution.” Even before Charles Darwin published “On The Origin of Species,” where he laid out his case for evolution, scientists were postulating that an increasing reliance on technologies like medicine and shelter had a negative effect on the species, making us less able to survive a state of nature. Check out the films “Wall-E” and “Idiocracy” if you want some examples.

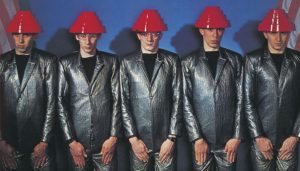

Devo named themselves after the devolution they saw in the cultural race for the bottom all around them. A species of hunters and farmers and makers and inventors was rapidly becoming a species of consumers.

Devo

Everything was a product, even happiness and satisfaction. Even the counter-cultural revolution of the late 1960s had been commodified. Hippies had become simply another marketing demographic.

Devo’s version of “Satisfaction” is really different from The Stones.’ In place of Mick Jagger’s self-possessed swagger is Mothersbaugh’s robotic awkwardness, giving voice to an anxiety absent in Jagger’s confidence. In the Stones’ version, it doesn’t feel like Jagger minds his frustration at all, in fact, he seems to rather enjoy it.

In the Stones’ version desire sounds natural, organic and good. The song was deemed so libidinous that it was banned by many radio stations at its time of release. The Stones were suggesting musically that there’s nothing wrong with pursuing something that feels good.

In Devo’s machine-like version, desire becomes robotic and programmed behavior arising from a will that is not quite our own. This sinister recasting of desire is a powerful critique, hinting at the way marketing and consumerism influence and ultimately take over the most intimate aspects of our existence. We are compelled to desire what society tells us to desire through the medium of marketing. Advertising is a seduction.

The band’s cybernetic convulsions in the video further emphasize the robotic nature of consumerism. What if we cannot satisfy our desires because they are not ours to begin with? What if our desires are simply programmed into us by the ceaseless barrage of advertising we’re exposed to?

In the video, Mothersbaugh is wearing swimming goggles, which add to his ultra-nerdy anti-fashion. I always thought the rest of the band was wearing 3D movie glasses. But then I got my eyes dilated and the ridiculous paper glasses the optometrist sent me out into the world with looked just like those. Their eyes needed shielding from retinal-searing media overload to whom they’re being exposed.

The song and video are full of tension: between desire and the social duty of restraint, between a solid groove and spazz attack, between the epitome of rock and roll cool and pocket-protector geekery, between the freedom to choose and an imprisonment to a programmatic lifestyle. But I think the real tension in the song is between the pursuit of our own innate desires, which can be satisfied, and the desires created within us by our culture and the media we are immersed in. Those desires, by their very design, can’t get no satisfaction.

Follow writer David Gill at Twitter.com/songotaku and Instagram/songotaku.