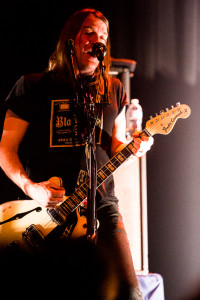

Q&A: The Dandy Warhols’ Courtney Taylor-Taylor on writing cool songs over slick ones

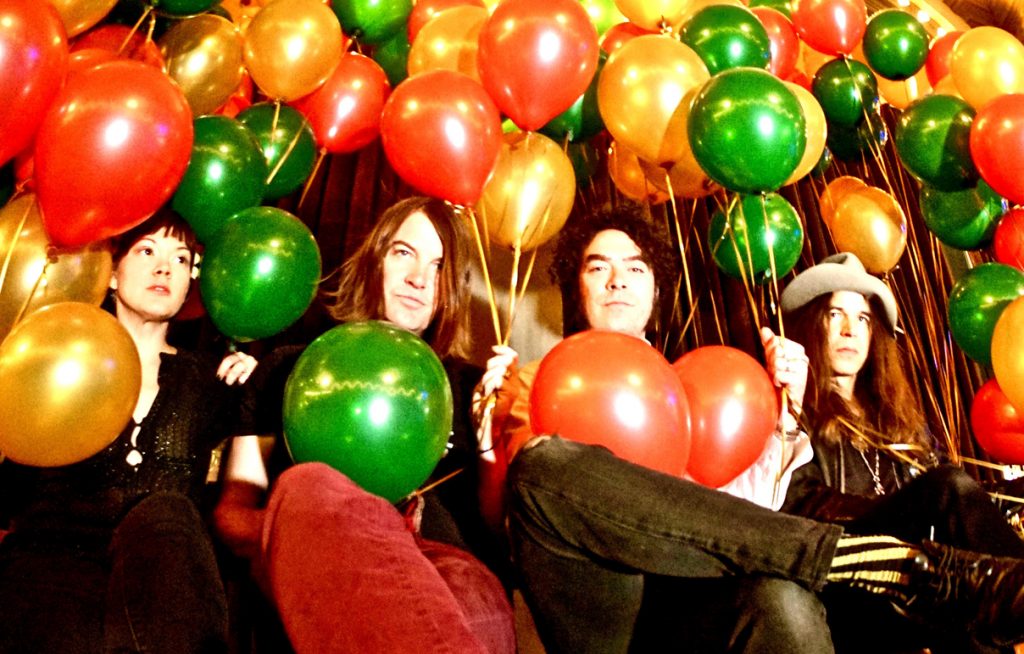

The Dandy Warhols

Every musical decision Portland alt-rockers The Dandy Warhols have ever made, they’ve tried to make in an effort to rebel against what was expected not only of themselves, but of artists in general.

BottleRock Napa Valley

May 24 to 26

Napa Valley Expo

Tickets: General admission $160-$360.

There were times when frontman Courtney Taylor-Taylor, guitarist Peter Holmström, keyboardist-bassist Zia McCabe and drummer Brent DeBoer were able to strike commercial gold, such as with their third album, 2000’s Thirteen Tales from Urban Bohemia. Other times they veered seemingly purposefully away from mass-appeal. To succeed commercially while still upholding his artistic ideals is high on the list of goals for Taylor-Taylor.

“To stand out sonically is an emotionally powerful, clarifying act. But, you will suffer for it,” he said in a recent phone call from his home. “That’s just inherent in the equation, as well. You will not be taken seriously as a Top 40 singles-producing musical act. You’ll be definitely flagged as being somewhat avant-garde or quirky.”

The Dandy Warhols members all have families now and are pickier with where and when they tour, but they’ve always crafted their songs carefully. Now marking 25 years as a band with a 10th studio album, Why You So Crazy, the band is hitting the road for a few weeks that will culminate with their first performance at BottleRock Napa Valley.

The new album is another seemingly disparate collection of songs, from a straight-shooting tale of small-town life (“Motor City Steel”) to a rollicking McCabe-sung story of a marriage at rock bottom (“Highlife”), the trippy “Terraform,” psychedelic “Be Alright” and “Next Thing I Know,” glitchy and dramatic “Forever,” religious-imagery-heavy “Sins Are Forgiven” and “To the Church,” and even a six-minute classical piano piece played by McCabe—“Ondine”—that Taylor-Taylor points out just entered the public domain in 2019 after turning 100 years old.

Taylor-Taylor, speaking while his young son played nearby, talked about his passion for wine and the good life, balancing the band members’ lives with The Dandy Warhols’ music, and making music that rebels against the status quo.

RIFF: You get to be pretty picky with where you play. How did you go about planning your other destinations? You don’t go on any long tours these days.

Courtney Taylor-Taylor: We have a number of younger kids. I think it really hurts little self-esteem. It affects them in a way that I don’t want having a band affecting them, you know? Maybe I’m just more sensitive than most rockers. But it just didn’t feel right. I couldn’t do it anymore. I can’t do that to a little person. It made us realize a lot of things. It seems like the more time you spend on a tour, the more money you’re flushing down the toilet. So it did force us to become a lot savvier about how we tour—so that we’re not doing short tours and losing money. To try to make it as fun as we possibly can, and as profitable as we possibly can, I think that had a good effect on our vision of ourselves overall; what the band is.

Was it always a foregone conclusion that you get to album No. 10? Or, did it come together accidentally?

We own the studio, so we never stop recording. We look at what’s done and what’s half-done, what’s just started, and every few years we notice that, “If we take from this piece through this piece of music,” and “We complete these, and these, and these,” that’s a whole record.

So let’s stop; let’s just really focus on those things, and make that our next record. And everyone kind of agrees on it, or doesn’t agree. … But, yeah there just comes a time every two, three years where we just have enough music where we could call it a record. We’ve got five things underway that have been underway for the last couple years that will be on the next record. When that one comes out, there’ll be three, four, five things— seven things underway that will then be the next record. It just doesn’t seem to ever end because we really like fooling around in the studio. It’s an amazing thing to do.

On the new album, there’s so many different textures on the songs and so many different vibes. It sounds like the songs came from different times of your band, or different eras.

We’ve heard that about every record we’ve ever put out. I think over time when you look back on our records, they have a very distinctive uniformity to the overall sonic size and shape. But, inside of each record, of course, there are many different styles and motions and perspectives. Once time has passed, it does seem more cohesive. As cohesive to other people as they seem to us. To us, obviously, they’re our thoughts and feelings and they’re our lives, so they do seem very cohesive in our minds.

Was there anything that you wanted to accomplish with the record? I’m trying to avoid the, “how does it feel to be together for 25 years” question that everyone has been asking. But, was there anything that was left that you guys wanted to accomplish, or are you just having fun being together at this point?

I don’t know. There’s always an idea or a vision to the whole thing. This was definitely all about when it came to the mixes, about having a lot of clarity and negative space in the high end; in the treble and high-end frequencies. Other producers—only, really, other producers—tend to notice that there aren’t really any hi-hats or any cymbals in the record. Also, other producers notice that the snare drum sounds are completely whack.

This would never be accepted in most recording situations. Those were two very important things for me: That there’d be some sonic act of rebellion. Every record has had to have had that element. It’s part of our nature. This is just a specific act of rebellion on this one—how to learn to command the high frequencies on the record and to be in control of them. Those were kind of the sonic priorities. Obviously, any real artist would never let the medium itself inhibit the emotional power or depth of expression. So, therein lies the rub.

It is always a learning experience, taking this number of songs and turning them into a record that is its own set of series of tasks and problems and hurdles to overcome. Turning super-problems into superpowers—that’s the name of the game, I think, when it comes to life in general. I would say [it’s] doubly so and more obviously so in the studio.

You’re saying, “What wouldn’t anybody do? Let’s try and do that but make it sound good and have it connect with people.” That’s is a very tough challenge.

And have it work to our advantage, is really the thing. Yeah, you’re exactly right. What would nobody do? What would people not do? What do people actively try to avoid? Then do it and “how to then patiently carve and nudge and move it around, and add and subtract things.” Until it really is working to your advantage. You’re avoiding current idiosyncrasies of your era and that’s always emotionally a power move. To stand out sonically is an emotionally powerful, clarifying act. But, you will suffer for it. That’s just inherent in the equation, as well. You will not be taken seriously as a Top 40 singles-producing musical act. You’ll be definitely flagged as being somewhat avant-garde or quirky.

Everything I know about you guys tells me that you never cared about that anyway.

Well, it was quite surprising when we were commercially successful. We always just wanted to have the dudes in Bauhaus like us. And wanted to meet David Bowie. We just assumed that if we could do that, then the financial reward would just be there. You could make a living; you could do it; you would not have to work at a nightclub, or wash dishes at a bar, or be a bartender. You could just be a musician if you worked really hard and were very honest with yourself about what you’re doing, and you make really fucking cool records.

If you have a decision to make; to err on the side of slick in hopes on having a hit, or in hopes of just putting out a cool record, you always err on the side of cool. Always. You never err on the side of slick because if you fail; if you miss something and you fail at that, that’s embarrassing yourself publicly. And that’s not worth the risk at all. People are always out there trying to call you out and trying to make you look stupid. There’s just always somebody out there to get you. So, you’ve got to play it pretty tight, and you’ve got to be clear on what you are and aren’t, or I think or you’ll find yourself embarrassed.

It’s like, if you’re going to go down fighting, it’s better to go down with the sword stabbed through your heart than through your ass, right?

Yeah, right? That’s definitely our thing.

And then live, like at BottleRock, it’s not a studio, so it’s four cats with a bunch of instruments and an arsenal of really good songs. So, we don’t try to approach what’s coming out of the speakers in any particular way. We just try to make sure we have a “front of house” sound mixer guy, or girl, that understands our music and feels it, and can make sure that it just rocks. It’s emotionally powerful, it’s sonically trippy, and it’s just, physically, a big “fuck, yes.” And that’s what you expect. For anyone who’s going to BottleRock, that’s what’ll happen there. It’ll be real instruments. We will not be having a lot of digital backing tracks, and it won’t be slick.

There will be a lot of music coming out of those speakers on that weekend that is coming off of the digital platform. … A lot of huge, huge Top 40 bands. And we won’t be that. We will be the other thing that happens—dudes and chicks playing old-fashioned instruments; old-timey music. Rock is an antique form of music now. Psychedelic rock, even more antique, you know?

I want to ask about “Motor City Steel,” which is a love or anti-love song.

It’s not either. No, it’s really just an occurrence that I noticed when I lived in a small town in southwest Washington for seven years. I thought that this is really particular, or I mean, this is really peculiar that nobody has written a song about this thing that now happens. … Small town people are grown up at 26 years old. They’ve got a 5-year-old and a 7-year-old by then.

It really took the children that were born around the millennium to get old enough to be living on the web. Around 2012, 2013, you noticed that boys are tending to look at fishing gear, guns, truck parts, cross-compound bows, and girls are looking at a fashion week in New York or Paris. That leads to other things and other far-away places. We ended up having a lot of the most popular girls in town just up and move away. Their boyfriends were like, “Well, we’re supposed to get married; I mean we’re 22 years old. Everyone is married already.” My peer group in that small town was 40-year-olds that were grandparents.

So, that’s what that song’s about. And that particular girl—their names aren’t actually Travis and Ricky, but they’re a real couple. They’ve got two kids now, but they’re significantly older now. She didn’t actually go to Paris, she went to New York, and cut hair for a couple years, and then went to L.A. and tried to be like an alt-country singer. Then finally got that out of her system and came home. They got married, bought a house and back to business as usual. She had a few years where she went out and did it; saw the world. So, that’s what that song is about. It’s not really about pro or con of any of that thing.

The talking about the trucks thing with him and the chick who tended bar at the Mexican restaurant in that town got me actually going on the idea of how weird it is that the dudes just stay here. The chick that was the bartender she was like, [in feminine voice]: “I just trapped a stray axle in my F-150. So I can’t wait to get it out on the rocks again this weekend; I’m gonna go for deep mud this time. I’m so excited.” … She didn’t have any dreams of going to France or New York, or shopping on Rodeo Drive. Not at all. But there certainly were a lot of girls that did, that wanted to; that talked about it. And then a handful that actually up and moved.

I know that “Highlife” is not your song, but I wanted to ask about it. It sounds so fun, and it’s got some country vibe to it. But, there’s such a dark undercurrent to that.

Right; Zia’s a fucking rager. Well, that was when she split up with her husband. The lyrics are amazing. Those are the kind of lyrics you don’t come up with because you feel like you want to write a song. [That’s] the shit that comes out of you when you write a song because you have to—because you are going fucking crazy and you can’t stop trying to sort out your feelings 24-7. That’s why those lyrics are so good; because they could not come out any other way. They’re just Zia dealing with Zia.

Is that a harder one for her to perform, do you think? Or have you talked about it? Is that something that’s going to part of the set list?

Yeah, we rocked it on the European tour. I took a while because it’s probably the coolest bass line we’ve ever had in a song. And then she has to sing and play it at the same time. So, she had to simplify the bass line to get that and then really work on it so she could play and sing it at the same time. But not in the scene. But by the second gig, I don’t even remember thinking about it anymore. It’s just part of the show.

What appealed to you about playing BottleRock?

I’m a wine collector. I own a wine shop, and I’ve got a lot of friends that are wine makers in Napa. I’ve always just kind of been like, “Really? Why are we not playing BottleRock?” I am one of the most notorious wine guys in rock. That’s really weird. Finally, our manager emailed us one day and goes, “Hey, we’re on BottleRock.” And I go, “OK, thank you, finally, Jesus, about time!” What’s great is that we play Friday, which means we get to just hang out and drink for the rest of the weekend. Drink wine, go visit my friends’ wineries, maybe get some spa time in, a lot of hanging by the pool, and it’s just a lot of food and wine. I plan on putting on six, seven pounds over that weekend.

Follow editor Roman Gokhman at Twitter.com/RomiTheWriter.