REVIEW: Justin Vernon and Aaron Dessner look back at what could have been

Aaron Dessner (The National) and Justin Vernon (Bon Iver) join forces once again for their second Big Red Machine endeavor. It’s filled with so many guest appearances that you’re immediately reminded that no matter how personal it gets, music fosters community. That being said, How Long Do You Think It’s Gonna Last? is undeniably led by Dessner, whose need for self-expression is by and large the guiding principle across the bulk of the album, from the slow burn reminiscence of opener “Latter Days” to the delicate balladry of closer ”New Auburn.”

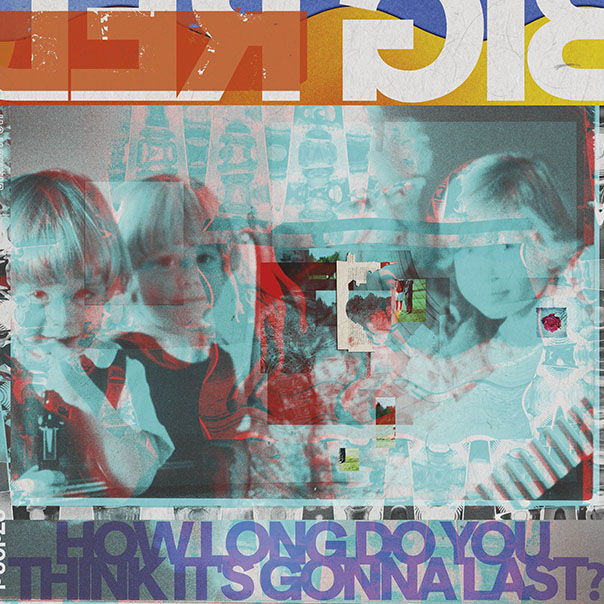

How Long Do You Think It’s Gonna Last?

Big Red Machine

Jagjaguwar, Aug. 27

8/10

Vernon’s contribution here is not negligible. In addition to being one of the principal vocalists–with remarkable performances on “Reese” and “Birch,” his songwriting peeks through the more experimental cuts on the album, injecting a welcome dose of unpredictability on tracks like ”Hoping Then” and ”Easy to Sabotage.”

His mark is also felt in the fuzzy storytelling of those tracks, painting quick sketches with one hand and erasing them with the other. There’s a free-flowing quality to those songs, giving rise to idiosyncratic lines like the evocative, “It’s on the edge of why I can’t sleep soundly” and the heart-wrenchingly simple, “I’m so easy to sabotage.”

How Long… rummages through the debris of memory to extract the formative moments that slipped by and are slowly resurfacing. It could have been a personal and almost selfish exercise, but Aaron Dessner and Justin Vernon are constantly searching for reciprocity at the same time.

“Would you ever light up with somebody like me?” Californian songwriter Ilsey asks on ”Mimi,” her voice closely shadowed by Vernon’s own tangential rumination. Later, La Force (Ariel Engle of Broken Social Scene) also yearns for companionship as she soars above a grounding drumming pattern. She calls out to “All of us together, this way/ All of us, a feather away.” Lyrics are kept sufficiently vague to let listeners wonder whether it refers to life on tour, far from loved ones, or an allusion to pandemic isolation.

”Hutch” is another trip down memory lane, a tribute to the late Scott Hutchison of Frightened Rabbit, and imagining different outcomes. The track may skew folky, but sounds more like Lana Del Rey’s “Ride” than John Prine or Bob Dylan. The Sharon Van Etten feature is also wasted through a choral-like inclusion that erases her signature vocals.

The song features the invisible third member of Big Red Machine: The Big Red Drum Machine. Programmed beats appear regularly across the track list, at times to the detriment of other compositional elements. On the one hand, they successfully evoke a simmering pot on the inspirational ”Birch” and are carefully laced throughout ”Renegade,” adding a thoughtful touch to an already dynamic collaboration with Taylor Swift (both Dessner and Vernon were involved in her last couple of albums). On the other, they lull listeners into unwarranted apathy on the last leg of the album, most notably on the uneventful ”June’s a River” and the needlessly long “Bryce.”

The most satisfying cuts reflect the journey into retrospection through melodic pathways that reach far and deep beyond their initial settings. The breezy “Reese” is concerned with reality over possibility (“What you shoulda been/ What you woulda been/ Well it ain’t no problem now”) gradually swells through phases of self-affirmation (“Well I’m more than that”) that are immediately mirrored in the growing instrumentation with subtle saxophone licks, enchanting backing vocals by Lisa Hannigan and electric guitar twirls. “Phoenix,” another standout, grows denser like an avalanche rolling down a gentle slope and picking up everything it encounters on its way down. It glides by like a celebration, leaving fields of pure, unadulterated admiration in its wake.

When Anaïs Mitchell asks, “Who are you to listen?/ Who are you to care?” on album closer “New Auburn,” it feels like the final blow to an already frail fourth wall. It’s a brilliant way to end an album that’s betting on its ability to include its audience along its meandering progression, and that succeeds in doing so at nearly every turn.

Follow writer Red Dziri at Twitter.com/red_dziri.