REVIEW: Florence and the Machine anticipate the future on ‘Dance Fever’

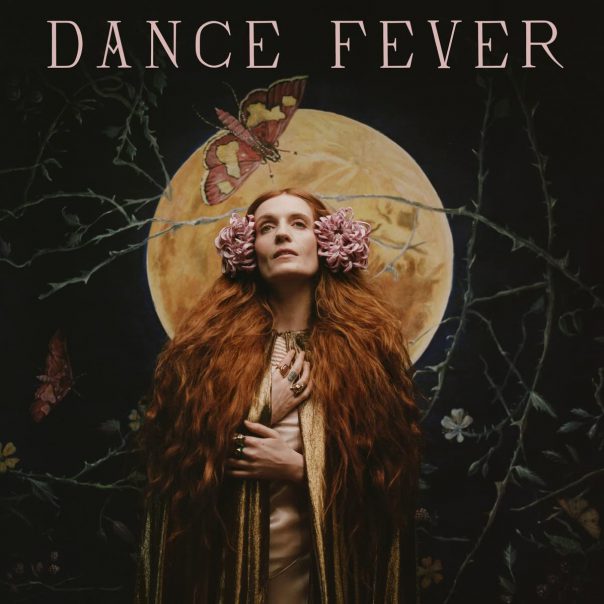

Florence and the Machine, “Dance Fever.”

Florence Welch has always been one to embrace the avant-garde sides 21st-century pop music allows. With booming choruses, baroque lyricism and richly decorated videos, each of her albums has felt almost like an elaborately layered oil painting brought to life. With Florence and the Machine fifth album, Dance Fever, she’s crafted another LP that looks to the past to celebrate the future.

Dance Fever

Florence and the Machine Polydor, May 14

8/10

Welch was inspired by films like Midsommar and the 13th-century choreomania (or dancing mania), a social movement where large groups of people broke out in dance, sometimes to the point of exhaustion.

The album’s third track is named after that movement.

“I don’t know how it started/ Don’t know how to stop it/ Suddenly I’m dancing/ To imaginary music,” she sings over the light snapping beat. The music begins to grow with powerful ambient pulses as she feels herself start dancing to death. Across its three and a half minutes, the song continues to build in pace and energy. Welch wrote the majority of the first half of the album with coveted producer Jack Antonoff, whose modern pop styles are apparent across the songs.

Antonoff’s influence is most prominent on “Free,” which sounds like it could fit onto a Bleachers album without listeners ever second-guessing its place. The beat is repetitive but eager as the song’s lyrics ratchet up with intensity.

Welch crafted the album looking forward to the days when her music could once again be played in nightclubs. She began production on Dance Fever right at the beginning of the pandemic and sought to make its sound anthemic and infectious. She succeeded on both fronts. Lyrics like “picks me up, puts me down” repeat in rapid succession and match Antonoff’s signature driving pop sounds, which are also present on Taylor Swift songs like “Out Of The Woods” or across Lorde’s Melodrama.

Album opener “King” is one of the most memorable on Dance Fever. “We argue in the kitchen about whether to have children/ About the world ending and the scale of my ambition/ And how much is art really worth,” Welch sings over steady drumming on the outstandingly composed opening verse. She crowns herself the king after denying her role as both a mother and bride. After the third chorus, the beats push at first and then subside for just a moment before she erupts into a vocalizing belt for 40 solid seconds.

Welch wrote “Cassandra” with frequent cowriter Thomas Hull (“Sweet Nothing,” “Ship to Wreck).” The song tells the story of Welch feeling like Cassandra, who endures the wrath of humanity as they shun her into the kitchen and treat her like they would Satan by placing crosses on their doors. She finds that heaven has lost its appeal as she sees that, “There’s no one left to sing to/ And all the Gods have been domesticated.”

Throughout the album—and in typical Florence Welch fashion—she crafts profuse and allegorical stories that could all be performed as spoken word poetry and would gain a standing ovation. To make the material that much richer, her vocal abilities are another force to be reckoned with as she belts and whispers, harmonizes and drones into the microphone.

The further you get into the album, the more it begins to sound like her breakthrough debut, Lungs, back in 2009. On “Heaven Is Here,” the music is animated with grunts and stomping that recalls her oldest tracks like “Howl” or “Drumming Song.” “My Love” follows in a similar style. She acknowledges her unparalleled songwriting abilities: “Words always made sense to me,” she sings. As the lights of a nightclub begin to spin and morph in color, the song replicates those feelings of alcohol seeping in and a brain fog taking shape. Welch searches in the bodies around her for a place to invest her love, only to find the skies and her arms empty.

In the final moments, she takes a flight to Memphis and searches for Elvis, another king. “Morning Elvis” is more of a slow burn than the album’s other songs. In an audacious comparison, she tells her friends that if they don’t see her again she’ll see them in heaven with Elvis. Florence and the Machine have produced one unique and memorable album after another, and Dance Fever does that again. It’s both thriving and progressive while continually drawing on imagery of Renaissance-style art and religious practices that preceded its release by centuries.

Follow Domenic Strazzabosco at Twitter.com/domenicstrazz and Instagram.com/domenicstrazz.