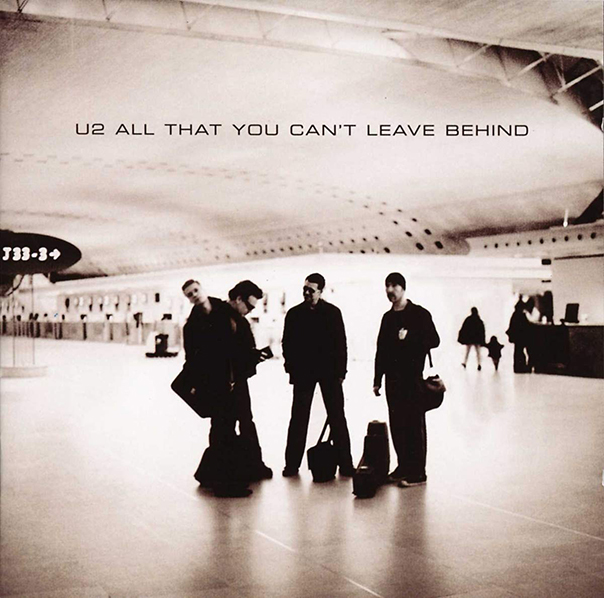

Two U2 nerds on the significance of ‘All That You Can’t Leave Behind,’ 20 years later

Twenty years to the day that U2 released its landmark album All That You Can’t Leave Behind, Roman Gokhman and I jumped on Zoom to talk about what the album means to us as fans, its cultural impact and legacy, and how it changed the course of U2’s music–for better or worse–in the two decades that followed. After lifetimes of taking their U2 fandom to questionable extremes, we are uniquely qualified for this nerd-tastic deep dive. Gokhman has followed U2 on multiple tours and I am the not-so-secret identity of Barely Larry, drummer for U2 tribute band Zoo Station. Gokhman started showing up at my gigs about 15 years ago, and we’ve been stuck in a moment ever since.

Skott Bennett: One of the things that I’ve noticed about this record is, like a lot of older U2 records: people attached memory to this album. It’s the weirdest thing. I don’t know if it’s because of the proximity to 9/11, the proximity of the 21st century starting, but this seems like a moment of everybody cleaning house emotionally and then letting something new in. So I find that this might be the last U2 record that most people realize they remember what they were, who they were, what they were doing when it came out. I don’t even know if we can say anything like that about the records that came after this.

Roman Gokhman: To me, this is the third tentpole for U2. So it’s one of the three best albums that they’ve made; however you want to arrange those. There’s definitely memories tied to the time that it came out, how it’s tied to 9/11. … To me, there is this record, then 9/11, and then Springsteen’s record that kind of hold that event up on both ends. This was the very first time that I’ve followed any band, the first time I’ve seen a band more than once. It was also the first time I was excited ahead of time before an album release. This was also the album where I started trying to chase that U2 interview that I’ve never gotten. I do remember where I was. I remember the places that I visited. I still have friends that I met because of this album, and that’s when I went from being a U2 fan to being a big U2 fan.

What it was like outside of “The Heart” stage on U2’s Elevation Tour. Tacoma, Wash. April 2001,

Bennett: It must be amazing for you; following them on tour and making those types of friends with similar interests and just kind of building a family—which is a theme throughout this entire record itself—and see, “What are you going to move forward with in the next part of your life? How much looking back are you going to do? What are you going to leave behind, and what are you going to move on to?” Just hearing you talk about it like that; it’s like the perfect record at the time.

I remember going through a period of some pretty tough change. I was in a band for most of the ‘90s that I was just so incredibly focused on and knew that we were going to be breaking through any minute. It never happened. The year before this came out, the band split up. I was dealing with that for a long time. Not to get too much on the therapist couch, but it was a big disappointment.

I was living in San Francisco, and I had been there for about eight or nine years, and I only ever lived in the same flat. I loved this flat. Roommates came in as roommates left as family, and I had friends move in for a while. There were so many great memories attached to this flat. … and we were getting evicted during the first dot-com housing crunch in 2000. And I remember hearing “Beautiful Day” when it came out, and the line, “There’s no room/ There’s no space to rent in this town.” I just remember hearing that, going “Bono understands!”

Then the other thing I remember is there was a big U2.com site redesign leading up to the release of this record. And one of the things that they did was they had little audio clips of seven songs and just having my mind blown and hearing 10 seconds of “Elevation” and just going, “Oh, my God, this record is going to be amazing.” It just built anticipation for me. I couldn’t wait for this record as a fan, and with all the things going on in my life and the themes of this record, just like for many people, it came at the right time. Then, of course, times got even harder. The country is attacked, and everything’s turned upside down, the economy’s turned upside down. I had friends who lost family in 9/11, who bonded with this record, and for a lot of people, these songs were what got them through.

Gokhman: What do you think it is about this record that specifically caught on with people?

Bennett: I think the directness of it. I love when Bono creates the characters. I’m a big, big Achtung Baby fan. But then when they just they just came back with these really direct lyrics. They weren’t playing with irony. They weren’t playing with being a character. It just kind of seemed like a “no bullshit” album. I know that the phrase “back to basics” was kicked around a lot when this record came out. I don’t know if that’s entirely true. I mean, the first thing you hear on the album is a drum machine, so it’s not like they’re going back and making War again. I think there’s a there’s the directness from that kind of ties back to the some of the earlier records, but it’s delivered in a completely different way.

Gokhman: There’s songs on here that really convey messages that a lot of people were tied to back then: “Stuck in a Moment,” “Walk On,” “Kite,” “In a Little While.” There’s a song called “New York,” obviously, but nothing about this record was about or because of 9/11 because it came beforehand. It’s not like Springsteen, who wrote a reaction. And yet, other than last Springsteen record, this album is really something that a lot of people connected to it. At least a lot of white people around our age.

Bennett: Yeah, for sure. I think it’s a better record because of that. I think that knowing the way they fuss over things, if they had written “U2’s response to 9/11,” they would have fussed with it for years and years and years. So I think the fact that they kind of provided the soundtrack to come home to during a really confusing time. Just to comfort people with a song like “Walk On,” … it’s no wonder why it resonated the way that it did.

Can we talk a little bit about what it meant for the band?

Gokhman: Yeah.

Bennett: This is a really interesting time in their history. Obviously, they spent the ‘90s and deconstructing themselves and reinventing themselves with Achtung Baby and Pop and the subsequent tours. That whole experiment somewhat ran out of steam at the end of Pop, at least commercially. I know they sold a ton of concert tickets, but the album didn’t perform well. And then they go away for a couple years. And I remember when they would appear on the Grammys in the run up to the release of this record, and Bono saying things like, “We’re reapplying for the job of best band in the world again.” It’s kind of sending a signal that, “If you were confused by the last record or two, U2 is back to what you associated with us.” That bugs me. I don’t think they had anything to apologize for. It’s kind of like a subtle apology tour for people who didn’t get Pop. I understand why they had to come back to this point, to reconnect with the general public and become culturally significant. That’s something they’ve always been after, but I also think it’s kind of a shame because Pop, for all of its faults— I don’t think the band was willing to take risks on an album after that record.

I think the lesson that they learned with this album was that they should spend a lot of time thinking about what people expect from them, where in the ‘90s, they just didn’t give a fuck; they got really creative. You can say the same thing about The Unforgettable Fire, and just do this crazy artistic left turn, and everybody went with it. Then now you see, from 2000 forward, this kind of struggle between art and commerce with the band, and you can you can feel them kind of pushing into really interesting areas and then coming back. … Walking that fine line between being all things to all people and really pushing the envelope and being creative. I feel like they probably erred on the side of being all things to all people, more often than not, since this album. … I think it could be argued that they learned some of the wrong lessons, and this “all things to all people” phase of U2 is what we what we got. We did get some amazing tours out of that phase, and that’s been definitely been a high point. What do you remember about the Elevation Tour?

Gokhman: I saw Portland and Tacoma shows on the first leg. And then when they came back, it was after 9/11, I did the Phoenix, Vegas. I ended up flying to Miami. I remember the heart, obviously. That’s kind of the point where the B stages finally connected, and they’ve had an element of that circular stage ever since. I remember that it was so no-frills that after seeing a Popmart show, I was actually surprised how little bang a U2 tour could have. But then I experienced being inside that heart, and it all made sense.

“The Heart” stage on U2’s Elevation Tour.

So rather than the pyrotechnics and mirrorball lemons and huge screens and seeing that from far away like I was watching TV, I was being smashed in a group of 300 like-minded people who were basically experiencing the same high at the same time as me, that was the experience.

Bennett: This tour was pretty monumental when I saw it. I didn’t follow them around. I think I saw it every time it came to the Bay Area, which may have been four different times between San Jose and Oakland. It was innovative in a different way. … It was again, a shift for U2 and how they leveraged the relationship with the fans and the super fans. I remember there was this whole, “Are you going to get into the heart or not?” It kind of separated the casual fans from uber fans, literally with a barrier for the people that wanted to make a sacrifice to get close. And there’s been some element of that since then, which has been great, because it’s an actual, like tactile, physical, if you want to call it “spiritual,” experience that you’re giving to the people who show up. I think that other bands have versions of this, but I think U2 really knocked that out of the park. It’s like Christmas morning, in my mind, to get into that heart. I remember the sheer excitement of being that close, being around all those people that felt the same way, and then just being that close to the performance. It was mind-blowing.

Gokhman: It was the fans who had convinced me that inside the heart is where I needed to be. Up until that point, I was a fan, but not what I would call a diehard. Luckily for Popmart, they came to my hometown in Eugene, Oregon and made it very easy. I was a senior in high school then.

My few [Elevation] show was Tacoma, Washington and I had seats. I paid like the $200. I’m thinking, “I’m spending so much money, this must be the place to be.” Then for Portland, general admission was all that was available, so I paid $45 for a ticket. I showed up the morning of. I wasn’t even camping out yet, at that point. But that’s when I met the people, some of whom I still know today, who kind of started training me, from that point on, about what it is to be a U2 fan. The Portland show was April 15, 2001. I’ll never forget it, because it was Easter Sunday and that’s the day Joey Ramone died.

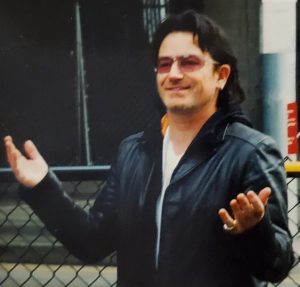

Roman Gokhman meeting Bono for the first time, in Portland, Ore., on April 15, 2001.

I still remember some of the specific lines that Bono sang to deviate from original lyrics. He called Ramone “my big brother.” Before that show there was a small crowd. The fans who were going to try to meet the band beforehand basically dragged me to the loading doc where the band came in, because I had no idea what was going on. And then when Bono walked up, as opposed to what happens a lot of times these days with a lot of crowding and pushing, everybody cleared out of the way so I could have a conversation with Bono for the first time. So that was my first direct connection with the band.

Bennett: It was the elevation tour in San Jose where Scotty, also known as Adamesque, had the idea of starting a U2 tribute band. The genesis of Zoo Station is from around this time. It didn’t get up and running until 2002. … So thank you, U2, for giving me my longest job.

I think it’s fair to say that the creative risks were fewer and further between after this album. There have certainly been great songs, but there’s been this tendency, like “We have to have a song that’s going to get on the radio, we have to start working with people from OneRepublic,” outside songwriters, with Will.i.am, for fuck’s sake. “We want to be current. We want the kids to like us.” I don’t think outside of the “Vertigo” single that that’s worked at all. It’s a shame because I think all that effort could have been spent chasing some kind of more out-there artistic idea. It’s made them more disciplined as songwriters, which is which is good, but I think, sonically and creatively, I think they take less risks. I think that’s a shame, although sometimes it’s led to some pretty great results. I wonder what we could have gotten if they learned a different lesson from Pop and wonder where we would be right now if they actually finished Pop properly and had a hit or two, and they had learned a lesson that they could really push the envelope.

Bennett: Let’s talk songs. “Beautiful Day.” I feel like this kind of bought the ticket to the next phase of their career. On a musical level, I kind of don’t hear it anymore because it’s so ubiquitous. It’s kind of hard to like sit down and actually pay attention to “Beautiful Day” because I’ve heard it so much. But in preparation for our talk today, I tried to say, “What was this like the first time I heard it?” I think in a lot of ways people associate the album after this, 2005’s How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb, as a reaction to grunge a decade too late. But “Beautiful Day,” if you listen to it, was quiet verses and then the explosive chorus. That’s almost like U2’s version of a Nirvana song because you’re really playing with dynamics.

I think it’s also it helps tell the story of the song. The verses are these very literally personal almost confessions. And then there’s this just explosion of joy in the chorus. So I think that their instincts as songwriters; everything is sitting on “Beautiful Day. Yes, we’re all at various levels of sick of it. The reason we’re sick of it is because it was a great song to break through on a cultural level.

Gokhman: It was so earnestly hopeful, which back then didn’t seem like a bad thing, at all. It just provided that straight joy, which was like the opposite of the irony that the band delivered on Pop.

Bennett: You love “Stuck in a Moment.” Why is that?

Gokhman: On the album, it just felt like Bono was talking to me. Certain lines on there are written in a way to connect with a lot of people on a personal level, but he never talked specifically about his issues, just about how he’s reacting to those issues. It’s just a very universal thing.

Bennett: It’s a pep talk. He wrote the song in response to the death of his friend, Michael Hutchence of INXS. It’s the conversation that he wished he would have had with him before it was too late. “Stuck,” I think, is a song that in the last year or so has just kind of taken on a new life for me because so many of us literally feel stuck in limbo right now. We lost touch with what time is, what day the week it is, because we’ve all been cooped up in our homes and dealing with this horrible existential threat. Seeing what’s going on this year has felt like five years. So we are like stuck in the moment we can’t get out of right now, and I think it’s another song that was popular to where I stopped hearing it for a while. But I heard it earlier this spring and it just really got to me in a way that it hadn’t since the album came out. I think it’s really prophetic in a lot of ways, and it really works right now. There’s U2 that has aged well, and there’s U2 that hasn’t aged well. This is a timeless song. It just seems like one of those melodies that’s been around forever.

Gokhman: “Elevation” to me is a pure adrenaline song. It’s about trying to make you feel a certain way.

Bennett: You know, the scene in the Queen biopic that came out last year? I’m sure this is all fictional, where Brian May says, “I want to write a song the whole crowd can participate, stomp their feet, clap their hands” for “We Will Rock You.” Like writing a song specifically for a live context. I can’t say for sure that that was their goal with this song, but it certainly comes off that way. You’ve got the wordless “whoo-hoo!” hook that everybody can get. You don’t need to know the words to sing along. You jump up and down. It’s definitely been a live standout. It’s interestingly placed in the album because of how it responds to the song before and how it sets up the themes after. It’s kind of like this release of joy, happiness, so it doesn’t get bogged down in some of the darker themes in “Stuck in a Moment,” but it’s also not as heavy as long as “Walk On.” So it’s kind of like this pause before the really deep material of the next couple of songs.

“Walk On” is definitely something that gets connected to 9/11 quite a bit. Do we need to get into the Aung San Suu Kyi thing because the song was written for her?

Gokhman: That kind of all went sideways on the band.

The song has the album title in the lyrics, so it’s as close to the title track as we get. Again, a lot of emotional connections. It’s like a list. It’s like U2 is packing a suitcase with all the things important to them and showing it to everyone.

Bennett: “Walk On” the heart of this album and everything else kind of orbits around it. When I hear this record, I’m putting myself in the band’s shoes, like, “This is what I want people to take from this experience.” This is also our first peek at the older, wiser, more fatherly Bono. Because of the nature of the song and the message of the song is how you handle tough times. It comes off very, very fatherly. I think his oldest kids must have been … 9 or 10 at this time. I almost feel like there’s a consciousness that starts to emerge here that starts to be in almost every U2 song after this. It isn’t the same guy storming the barricades with the white flag or wearing sunglasses. This is Bono sitting down, telling a story.

Gokhman: The transition between “Walk On” and “Kite,” I think, is one of the best in the U2 catalog.

Bennett: When I think about this song, I go right to the bridge. It might be some of the best singing of Bono’s career. “I’m a maaaaan. I’m not a chiiiiild.” It’s a high point in a career of high points. That honesty and vulnerability and the performance of that bridge. We didn’t get a lot of moments like that before. I think it might be his first overt song about being a father. I think about the song a lot. I think about my relationship with my kids and my dad and my stepdad. … It’s one of the best songs on this album and probably one of the best-executed songs. It really works well as a complete idea.

Gokhman: I think the album is so successful because it’s a complete album, even outside of the singles.

Bennett: You mentioned the singles, and then I’m looking at the tracklist, and this is the first four songs. That’s interesting to me; that’s something they did on Joshua Tree that 1-2-3 combination right out of the gate is your first three singles. And it’s interesting because once you get through those four singles, the record starts taking a turn. Obviously, “Kite” stands on its own, and “In a Little While” is interesting.

It’s a bit throwaway, but it’s very well executed. It matters. It means something. I think there’s three songs in a row with that dad Bono delivery. Is he singing to his wife, singing to friends, singing to his child? We don’t know, and it doesn’t matter, ultimately.

Gokhman: To me, the second half of the album is just as strong until you get to “New York.” “Wild Honey” is one of my favorites that I never skip when it comes up. “Peace On Earth” is like a heartbreaking lullaby. “When I look at the World” is very introspective. I really didn’t like “New York” until 9/11 happened and then Bono tweaked a couple words and suddenly it worked.

Bennett: I remember “New York” really standing out on the tour on enjoying it.

I’ve got issues from here on out. I think song for song, you go from “Beautiful Day,” all the way to “In a Little While;” it’s like just a murderer’s row of career highlights for U2—songs that work next to each other, songs that work on their own. You really bond with them on a personal level, and then, “Wild Honey” kind of turns a corner. Now it’s OK to be a little silly; that’s fine. But “Wild Honey,” combined with everything that comes after; the drop-off of the second half of this album is as steep as any of their albums for me, personally. “Grace” is a great closer. “When I Look at the World” feels like it just doesn’t have a chorus, and they’re kind of searching. “New York” almost feels like a sketch or a demo. On “Peace On Earth” … it was important for the band to make a statement, and I would never take that away from them.

The tragedy is when you look at the songs they left off this album, we could have had a completely different side 2. I would love to be the fly on the wall for the band arguments that resulted in the decisions that got them here. The songs that were not on this album.

Gokhman: It was released back then, I believe, as a standalone B-side. But “The Ground Beneath Her Feet” is just a beautiful, beautiful song.

Bennett: Yeah, one of their best. So when I talk about U2 scaling things back and not taking risks, when you look at the tracks they didn’t release you can hear some of those risks perhaps for the first time on this 20th anniversary edition [which the band later released as part of U2 iPod package and again last Friday as part of the deluxe reissue]. “Levitate” is really interesting, sonically. It’s a nice bridge between the ‘90s experimental electronic U2 and the more anthemic U2 that most people are familiar with. It would have been a great way to kick off side 2.

There’s another really interesting song called “Love You Like Mad.” It’s just kind of like this loose, jangly thing that could have been in the spot where “Wild Honey” is and would give that moment of lightness without being perhaps as silly as it gets.

Gokhman: To me, switching out some in favor of others … we might be sitting here, and I might be telling you that it’d be great if the original ones stayed on. I’m definitely with you on adding “The Ground Beneath Her Feet,” but not in place of anything. This was the case on some of the international versions. Adding that song on the record, would have made it much better record, but it was already a really good record.

Bennett: Some of the sonic explorations that they didn’t make, you hear a little bit of that in some of the songs that they left off the album. So I think they were there, but they certainly made a conscious decision to go in a different direction. This album is still a lot of people’s favorite U2 album. This album still matters to people, and we’re still talking about it 20 years later, so who cares what I think about side 2? It works for people.

Follow Skott Bennett at Twitter.com/skottbennett. Follow editor Roman Gokhman at Twitter.com/RomiTheWriter.