Third Eye Blind frontman sues former bassist over streaming royalties

Former Third Eye Blind bassist Arion Salazar photographed with Xeb at Slim’s in San Francisco on Jan. 6, 2017. Alessio Neri/Staff.

The frontman of Third Eye Blind is suing one of his former bandmates for alleged streaming royalties theft.

The attorney for the former band member, Arion Salazar, is countering that the royalties are his on the basis that Salazar was originally pressured by an attorney that did not act in good faith to give up numerous rights upon leaving the band, and also that the agreement itself did not specifically address streaming royalties.

Third Eye Blind performs at The National in Richmond, Virginia on Nov. 11, 2019. Courtesy: Melissa Pruitt.

“Arion didn’t get anything of value to sign everything away. He signed his rights away for something that was already his,” said Joe Singleton, Salazar’s attorney. “That’s a big problem. The conflict of interest is another problem. It was basically a fraudulent scheme to allow [frontman] Stephan [Jenkins] to own everything.”

The breach of contract lawsuit was filed on Sept. 19 by Jenkins and Third Eye Blind in Marin County Superior Court in San Rafael and seeks more than $25,000 in damages and punitive action.

It stems from a separation agreement Salazar originally signed upon leaving Third Eye Blind in 2009. The founding bassist of the band wrote or co-wrote numerous songs from the band’s first three albums, 1997’s self-titled album, 1999’s Blue and 2003’s Out of the Vein, as well as various demos.

How’s It Gonna Be? Founding Third Eye Blind members fight for right to acknowledge contributions

Read part 1

Jenkins and Third Eye Blind have become infamous for infighting and by 2009, following the departure of original guitarist Kevin Cadogan, Salazar was also forced from the band. Cadogan himself sued Jenkins in 2018 for a share of streaming royalties. That case was settled out of court, Cadogan said.

At the time of his dismissal, Salazar was being treated for drug addiction, Singleton said. It was around then that he signed a separation agreement that paid him $43,000 in exchange for any claim he had to the band and its songs, and “to once-and-for-all-time settle all matters between them,” according to the new lawsuit.

The original 2009 separation agreement referred to the royalty money Salazar was making as “gift income … in connection with the exploitation of musical compositions not written or composed by Salazar.” To give up any claims to future royalties, he received a payment of $21,500 upon signing and the same amount again six months later.

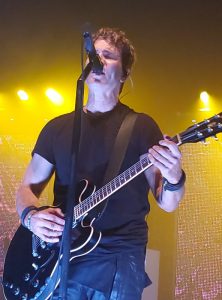

Stephan Jenkins of Third Eye Blind performs at Austin City Limits Live at the Moody Theatre on March 10, 2012. Courtesy: nanpalmero.com.

The agreement included language that each party had received guidance from legal counsel.

In early 2019, Salazar contacted SoundExchange, an organization that collects and distributes streaming royalties, and asserted his claim to the recordings on which he had played. SoundExchange, in turn, froze all payments to Jenkins and Third Eye Blind, requesting that the parties resolve their dispute by themselves or in court.

The new lawsuit is asking a judge to rule that the 2009 signed agreement must be followed, to assert that Salazar has no claims to streaming royalties from SoundExchange and rule that Salazar breached the agreement; additionally, all streaming royalties that have been withheld and damages—money—from Salazar for causing that delay and “bad faith dealing” would have to be paid with interest.

Neither Third Eye Blind’s attorneys, Napa-based Dickerson, Peatman and Fogarty, nor the band’s management returned numerous calls and messages seeking comment.

Xeb: Ex-Third Eye Blind duo adds another member to the club

Read part 2

But Singleton said that from the moment the bassist was forced from the band, Jenkins and the band’s representation acted in bad faith against him. That reportedly began with the 2009 separation agreement. The attorney who advised him was Thomas Mandelbaum—who also represented Jenkins and the band. Mandelbaum allegedly did not divulge a conflict of interest, though he clearly had one, Singleton said.

Third Eye Blind performs at Austin City Limits Live at the Moody Theatre on March 10, 2012. Courtesy: nanpalmero.com.

“His loyalty was mainly to Stephan and Third Eye Blind,” Singleton said. “They cooked up this agreement to have Arion sign it for the purpose of getting Arion to give up a bunch of stuff that he didn’t need to give up.”

Mandelbaum reached out to Salazar while the bassist was in drug rehab and had no money. His home had been foreclosed. The attorney offered Salazar a $43,000 separation agreement that would be funded by money won in a previous legal settlement related to the firing of Cadogan.

Jenkins had taken out an insurance policy to cover the potential dismissal of the guitarist, but after the firing, the insurance company refused to pay up. The band sued and won.

The litigation was funded by the band members themselves, Singleton alleged, with a portion of each member’s paychecks withheld. Salazar, like Jenkins, was a plantiff. The $43,000 dangled in front of Salazar to get him to sign away his claims to the band was already his; it was his share of the insurance lawsuit settlement.

“This money was never in dispute. Nobody ever said this wasn’t Arion’s money,” Singleton said.

Singleton said Mandelbaum and Jenkins tricked Salazar into signing the separation without legal guidance. While Salazar had Mandelbaum technically representing him, the lawyer’s interests were fully with Jenkins, he alleged.

“They gave him an agreement that says 20 different things in it that wasn’t part of [what was originally discussed], and Arion was in a place where he didn’t understand any of it. … Mandelbaum … had a conflict of interest and didn’t disclose that,” Singleton said.

Mandelbaum’s relationship with Third Eye Blind and Jenkins eventually deteriorated. He was himself sued by not only Cadogan but Jenkins. He is no longer affiliated with the band. In a recent phone call, he declined to comment for this story, neither about the ongoing litigation in which he’s named nor about the original agreement.

“Even lawyers need lawyers, and I’d probably need to get the advice of counsel, because among other things, I’m bound by certain confidentiality provisions,” Mandelbaum said. “This is not a universe I really want to go back to, to be honest with you.”

For a decade, Salazar believed he had lost all claims to royalties for the songs on which he played, until he showed the agreement to Singleton.

“It says ‘Arion gives up any right to any royalties he would receive from Third Eye Blind. … But SoundExchange royalties don’t come from Third Eye Blind. They’re 100-percent independent. … They collect money outside and pay it to … working musicians who have recordings that they performed on. When those are [streamed], they collect money on their behalf. They collect money on the record companies’ behalf, too, but that’s a whole separate thing.”

Third Eye Blind performs at Artpark in Buffalo, New York on July 3, 2019. Courtesy: Stephen J. Coia.

SoundExchange is a nonprofit collective rights management organization designated by Congress to collect and distribute digital performance royalties for sound recordings. It was founded in 2000 as a direct result of 1998’s Digital Millennium Copyright Act. The act allows service providers to stream artists’ songs in exchange for royalty payments.

Half of the proceeds SoundExchange collects goes to record labels. Another 45 percent is split among the artists and musicians.

“A lot of musicians don’t even know about SoundExchange. Arion didn’t either, at first,” Singleton said.

In February, Salazar asserted his right to 25 percent of the musician share royalties for the songs on which he performed.

SoundExchange is used to dealing with ownership claim disagreements and has a department that handles them, said Sam Harper, the organization’s vice president of communications.

“We don’t get involved because it’s for the band to decide among themselves,” Harper said. “How those are split is up to the band. We respect the decisions they mutually come to. We will, at times, hold royalties if there is a dispute … until the situation is resolved.”

Resolving the dispute is accomplished by the artists, by arbitration or through court order. The organization just recently released a set of online tools for record labels to manage overlapping claims of sound recordings themselves.

Stephan Jenkins of Third Eye Blind performs at Bill Graham Civic Auditorium in San Francisco on June 15, 2019. Courtesy: Melissa Pruitt.

In another wrinkle, Singleton alleged that Jenkins previously went to SoundExchange and told the organization that the band had decided to split up its own royalties, and that all checks should be sent to the band’s corporation—without Salazar’s knowledge.

“The Third Eye Blind people filled out a form with SoundExchange saying, ‘None of the musicians get anything; we own it all. We all agreed that we would collect it together and divi it up later’—which is a lie,” Singleton said.

Harper acknowledged that such a form exists but said he was unsure how SoundExchange would verify that all of the parties involved were actually in agreement to split up the royalties that way.

“We can pay the members of a band individually, or we can pay through the corporation of the band,” Harper said.

Jenkins’ lawsuit claims that the 2009 agreement covers SoundExchange royalties.

“Salazar voluntarily and willingly gave up any claim to SoundExchange royalties,” the suit states.

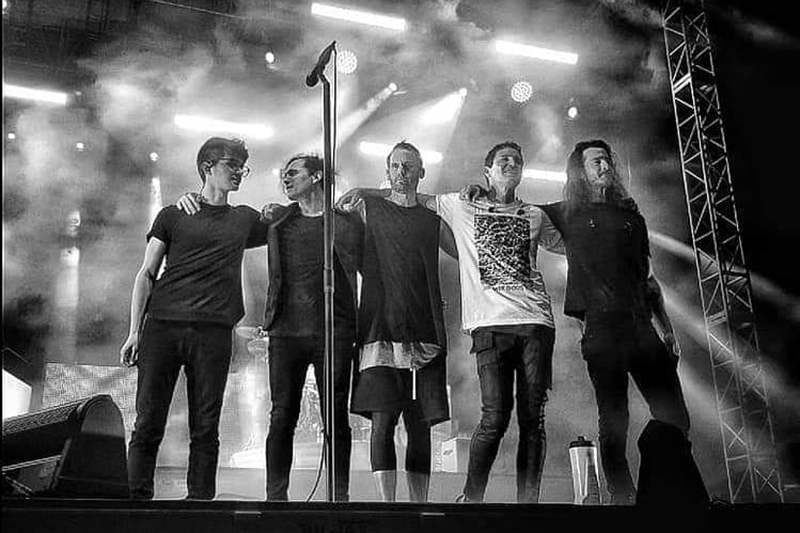

L to R: Kevin Cadogan, Tony Fredianelli and Arion Salazar photographed at Slim’s on Jan. 6, 2017. Alessio Neri/Staff.

Jenkins and former members of the band have often been embroiled in legal disputes. In 2016, Cadogan and Salazar formed a band, later adding former Third Eye Blind guitarist Tony Fredianelli and performing as XEB. This prompted numerous cease-and-desist letters from Jenkins.

Cadogan said he could could not speak about the resolution to his royalties suit against Jenkins, which was resolved in April 2019, due to a confidentiality agreement. He did say the suit sought his share of royalties that had been going directly to Jenkins.

“I also had a sound recording copyright claim regarding Jenkins’ release of our 1994-95 demo for the 20th anniversary album, which was done without my knowledge,” Cadogan said.

He’s also left XEB.

“I can’t discuss how [the court case and resolution] relates to XEB,” he said. “I am grateful to all the fans that came out to see our XEB shows. We brought the debut album live to over 43 cities with the 20th anniversary tour, and even though there were some real challenges it was an unforgettable and very healing experience for us.”

Follow editor Roman Gokhman at Twitter.com/RomiTheWriter.